Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Liver metastases, also known as secondary liver cancer, happen when cancer cells spread from their original location to the liver. This is frequent due to the liver's blood filtering from different body parts. Liver metastases are more common than primary liver cancers, and they have a significant impact on patient prognosis and treatment approaches.

Liver metastases, which occur when cancer cells spread to the liver from their original location, can arise from various primary cancers. The most common sources include colorectal cancer, with about 50% of patients developing liver metastases; breast cancer, where 20-40% of patients experience this complication; lung cancer, which sees liver metastases in 30-50% of cases; and pancreatic cancer, where liver metastases are found in 60-70% of advanced cases.

Causes & Risk Factors

What are the risk factors for liver metastases?

The risk factors are closely tied to the original cancer site. The most significant factors include:

- The advanced stage at diagnosis. Patients diagnosed with their cancer at later stages face a higher likelihood of developing liver metastases.

- Tumor aggressiveness. Rapidly growing (high-grade) tumors demonstrate a greater tendency to spread and metastasize to the liver.

- Genetic factors, including specific genetic mutations, such as those in the KRAS and BRAF genes, have been associated with an increased risk of liver metastases in colorectal cancer patients. For instance, KRAS mutations are found in around 40% of colorectal cancers and are linked to a poorer prognosis and higher rates of liver metastasis.

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) increases colorectal cancer to metastasize to the liver by about four times [Frontiers of Oncology, 2020].

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting liver metastases?

Patients with liver metastases may experience a range of symptoms. The liver's impaired function can lead to jaundice, causing the skin and eyes to appear yellow. The enlarged liver may also be noticeable upon physical examination. Many patients report abdominal pain, typically in the upper right quadrant. Significant, unintentional weight loss and feelings of fatigue are common. Nausea, sometimes accompanied by vomiting, may also occur.

Diagnostic Route

When, where, and how should the liver metastases be detected?

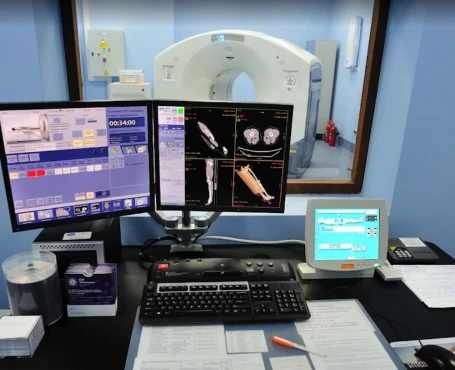

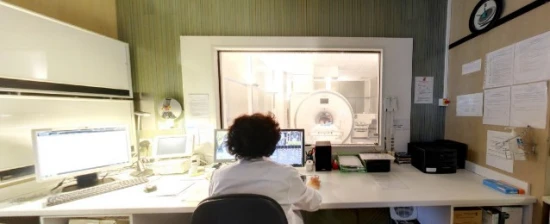

Diagnosing liver metastases involves several key steps. Firstly, imaging tests play a crucial role. CT Scans and MRIs are the primary modalities, offering high sensitivity and specificity for detecting liver lesions. PET Scans can also help identify active cancer cells throughout the body. Additionally, ultrasound is often used initially due to its accessibility and cost-effectiveness.

Next, a biopsy is performed, where a sample of liver tissue is examined under a microscope to confirm the presence and the origin of metastatic cancer cells. Finally, blood tests are conducted to assess liver function and measure tumor markers like CEA for colorectal cancer and CA 15-3 for breast cancer.

Treatment Approaches

What are the options for managing liver metastases?

Depending on the primary tumor origin, the following approach protocols are applied for the liver metastases. Multiple factors influence tumor cells' sensitivity to certain medications because various targets are under the scope of different liver metastasizes-associated cancers [ESMO, 2022].

Colorectal cancer liver metastase treatment

For patients with colorectal cancer that has metastasized to the liver, several treatment options are available. Surgical removal of the liver metastases is often the first-line therapy and can potentially provide a cure, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 25-40% after resection. Even in recurrent metastases, repeat surgery can offer similar survival benefits.

In addition to surgery, chemotherapy regimens like FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, combined with targeted agents such as bevacizumab, are effective first-line treatments and can achieve response rates of up to 60%. For patients with KRAS wild-type tumors, second-line combination therapies involving cetuximab have shown 20-30% efficacy rates.

Furthermore, targeted therapies like bevacizumab and cetuximab have been found to improve survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, with bevacizumab adding a median of 4.7 months to survival when used in combination with chemotherapy.

Breast cancer liver metastases treatment

For patients with breast cancer that has spread to the liver, several treatment options are available. Hormonal therapy is often the first-line approach for hormone receptor-positive tumors, with agents like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors providing disease control in 40-60% of cases. If the disease becomes resistant to these hormonal therapies, fulvestrant or CDK4/6 inhibitors like palbociclib can be effective second-line options.

Chemotherapy is another crucial component of the treatment strategy. Anthracyclines or taxanes are commonly used as first-line chemotherapies, achieving 50-60% response rates. For patients who have previously received anthracycline or taxane-based chemotherapy, capecitabine or eribulin can be used as second-line options, with 20-30% response rates.

In addition, targeted therapies have proven to be highly beneficial for specific breast cancer subtypes. Trastuzumab, a targeted drug for HER2-positive tumors, significantly improves outcomes. Furthermore, combining trastuzumab with pertuzumab and docetaxel has increased median survival by 16.3 months.

Lung cancer liver metastase treatment

For patients with lung cancer that has metastasized to the liver, chemotherapy plays a crucial role in management. First-line platinum-based regimens typically achieve response rates around 30-40%. Additionally, second-line options like docetaxel or nivolumab can provide additional treatment opportunities for those with progressive disease, although the response rates tend to be lower at 10-20%.

Furthermore, targeted therapies have emerged as an essential strategy for lung cancer liver metastases. Drugs targeting specific genetic mutations, such as EGFR inhibitors for EGFR-mutant tumors and ALK inhibitors for ALK-rearranged tumors, have demonstrated impressive response rates of around 60-70%.

Pancreatic cancer liver metastase treatment

For patients with pancreatic cancer that has spread to the liver, chemotherapy remains an essential component of the treatment approach. Standard first-line regimens like FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel have demonstrated 25-35% response rates. If the disease progresses, second-line options such as liposomal irinotecan combined with 5-FU and leucovorin can be considered, although the response rates are lower at around 7.1%.

In addition to chemotherapy, targeted therapies have also emerged as a promising strategy for specific pancreatic cancer subtypes. PARP inhibitors, like olaparib, have been found to provide a significant survival benefit for patients with BRCA-mutated tumors. These medications inhibit PARP, a protein in cells that assists in repairing damaged DNA.

Besides specific approaches for treating liver metastasis with different origins, there are two additional groups of therapeutic interventions, such as radiation therapy and interventional techniques [University of Tennessee, 2024].

Radiation therapy:

- External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) is used primarily for palliation to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Response rates can vary but typically offer significant symptom control.

- Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (STBR) provides high-dose radiation precisely to liver tumors, achieving local control rates of around 70-90%.

Interventional Techniques:

- Radiofrequency ablation is effective for small tumors, with up to 85% local control rates.

- Transarterial chemoembolization combines chemotherapy with embolization to block blood flow to the tumor, achieving partial response rates of 35-55%.

Prognosis & Follow-up

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with liver metastases?

The prognosis for patients with liver metastases can vary significantly based on the type of cancer, the extent of liver involvement, the patient's overall health, and their response to treatment. For individuals with colorectal cancer that has spread to the liver, the median survival typically ranges from 20 to 30 months. Still, surgical removal of the liver metastases can offer better long-term outcomes, with 5-year survival rates around 25-40% after resection.

For patients with breast cancer that has metastasized to the liver, the prognosis can be quite variable, with a median survival of approximately 18-24 months with treatment. However, the use of targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab for HER2-positive tumors, has been shown to extend survival rates.

The prognosis for lung cancer liver metastases is generally poor, with a median survival of around 6-12 months. Introducing targeted therapies for specific genetic mutations has significantly improved outcomes for some patients.

Pancreatic cancer with liver metastases typically has an inferior prognosis, with median survival rates ranging from 3 to 6 months. Yet, developing more effective combination chemotherapy regimens, such as FOLFIRINOX, has demonstrated improved survival rates, with some studies reporting median survival of up to 11.1 months.

Regular follow-up is crucial for effectively managing liver metastases. Follow-up protocols generally involve a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and blood tests to monitor the disease and detect recurrences early. The specific schedule can vary based on the primary cancer type, treatment received, and the patient's overall health.

During the initial follow-up, patients typically undergo visits every 3-6 months for the first two years after treatment. These visits may become less frequent, transitioning to every 6-12 months if the disease remains stable. The clinical evaluation includes physical examinations to assess the patient's overall health, liver function, and any signs of recurrence.

Imaging studies, such as CT scans and MRIs, are essential for monitoring the liver and detecting new lesions. PET scans may also be used for more comprehensive surveillance. Ultrasound can be used as an adjunct, particularly in resource-limited settings or for more frequent monitoring.

Blood tests play an essential role as well. Tumor markers specific to the primary cancer type, like CEA for colorectal cancer and CA 15-3 for breast cancer, are monitored. Liver function tests, such as assessing liver enzymes and bilirubin, help detect early signs of liver impairment.

After the initial two years, follow-up visits typically occur every 6-12 months. Annual visits may be sufficient for patients with stable disease or in remission. Long-term follow-up includes managing any chronic side effects of treatment, providing psychological support, and promoting lifestyle modifications to improve overall health and reduce the risk of recurrence. Screening for secondary malignancies is also an integral part of long-term care.