Overview

Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Breast cancer forms in the tissues of the breast – usually in the ducts (tubes that carry milk to the nipple) or lobules (glands that make milk). It occurs in both men and women, although male breast cancer is rare, making up around 1% of all breast cancer cases.

The earliest stage of breast cancer is non-invasive disease (Stage 0) – 20% from all breast cancer cases, - which is contained within the ducts or lobules of the breast and has not spread into the healthy breast tissue (also called in situ carcinoma). Invasive breast cancer – 80% from all breast cancer cases - has spread beyond the ducts or lobules into healthy breast tissue or beyond the breast to lymph nodes or distant organs (Stages I - IV) [cancer.net].

Invasive breast cancer is also categorized by how advanced the disease [ESMO, 2024; cancer.net]:

- Early (localized) breast cancer (66%) is characterized by a tumor that has not spread beyond the breast or axillary lymph nodes (also known as Stage I-IIA breast cancer). These cancers are usually operable, and the primary treatment is often surgery to remove the cancer, although many patients also have preoperative neoadjuvant systemic therapy.

- Locally advanced (regional) breast cancer (28%) – if it has spread from the breast to nearby tissue or lymph nodes (Stage IIB-III). In the vast majority of patients, treatment for locally advanced breast cancer starts with systemic therapies. Depending on how far the cancer has spread, locally advanced tumors may be either operable or inoperable (in which case surgery may still be performed if the tumor shrinks after systemic treatment).

- Metastatic (distant) breast cancer (6%) - Breast cancer is described as metastatic when it has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones, liver, or lungs (also called Stage IV). Tumors at distant sites are called metastases. Metastatic breast cancer is not curable but is treatable.

- Advanced breast cancer is a term used to describe both locally advanced inoperable breast cancer and metastatic breast cancer.

Sometimes, it is essential to know – both for patients and doctors – the subtype of breast tumors based on hormone receptor status (in the tumor cells) and Human Epidermal Growth Factor 2 (HER2) gene expression. And here is why:

- The hormones estrogen and progesterone stimulate the growth of some tumors. It is crucial to find out whether a cancer is estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PgR) positive or negative, as tumors with a high level of hormone receptors can be treated with drugs that reduce the supply of hormone to the cancer.

- HER2 is also a receptor involved in cell growth and is present in about 20% of breast cancers. Tumors that have a high level of HER2 can be treated with anti-HER2 drugs.

- Tumors that don’t have ER, PgR, or high levels of HER2 are described as triple-negative tumors.

Tumors can be classified into subtypes based on hormonal and HER2 receptor status as follows:

- luminal A-like – about 66% of breast cancers;

- luminal B-like;

- HER2 overexpressing – 15-20% of breast cancers;

- basal-like (triple-negative tumors) – 10-20% of breast cancers.

Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in women (6,9%, death rate 19.3 per 100,000 women per year) and occurs most frequently in postmenopausal women over the age of 50. About 13% of women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetime, making the incidence of the disease almost 130 per 100,000 women per year – about 311,000 new cases per year in the United States.

Based on the information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute [cancer.gov], in 2021, the prevalence of breast cancer in the U.S. - the number of living women with the disease – was 3,972,256 patients.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of breast cancer?

The precise cause of breast cancer is unknown, but several risk factors for developing the disease have been identified.

- Female gender

- Exposure to ionizing radiation

- Increasing age

- Having fewer children

- History of atypical hyperplasia

- Obesity

- Exposure to estrogens

- Alcohol

- Genetic predisposition (family history or mutations in specific genes – BRCA1 and BRCA2).

Women with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with breast cancer have twice the risk of developing breast cancer compared with a woman with no such family history. The risk is increased 3-fold if that relative was diagnosed with breast cancer before menopause.

Around 5% of breast cancers and up to 25% of familial breast cancer cases are caused by a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [Skol et al. 2016]. A woman carrying a BRCA1 mutation has a >60% lifetime risk of breast cancer, and more than 90% of hereditary breast and ovarian cancers are thought to be due to a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 [ESMO, 2023].

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting breast cancer?

- A lump in the breast

- An inverted nipple

- Rash on the nipple

- Discharge from the nipple

- Change in the size or shape of the breast

- Swelling or a lump in the armpit

- Dimpling of the skin or thickening in the breast tissue

- Pain or discomfort in the breast that doesn’t go away

- Skin redness

- Skin thickening

Diagnostic Route & Screening

When, where, and how should breast cancer be detected?

Breast cancer screening – a mammography test – is recommended for women starting at age 45 years. For those aged 50 to 69 - every two years; for those aged 45 to 49 - every 2 to 3 years; for those aged 70 to 74 - every three years [European Commission Initiative].

The most common symptoms of breast cancer are changes in the breasts, such as the presence of a lump, changes to the nipple, discharge from the nipple, or changes in the skin of the breast.

Initial investigations for breast cancer begin with a physical examination, mammography, and ultrasound scan. Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will also be performed in some cases. If a tumor is found, a biopsy will be taken to assess the cancer before any treatment is planned.

A doctor will refer a woman for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing based on her family history and ethnic background. If the patient is found to be carrying a mutation in one or both of these genes, she will be offered counseling during which her options for reducing the risk of developing breast cancer, such as a preventative double mastectomy and/or salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes), will be discussed (Paluch-Shimon et al. 2016).

Women who are found to be carrying a BRCA mutation and do not opt for risk-reducing surgery should be offered a clinical examination every 6-12 months from the age of 25 (or ten years before the youngest breast cancer diagnosis in the family, if earlier), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 12 months and mammography every 12 months from the age of 30 (Paluch-Shimon et al. 2016).

Treatment Approaches

What are the options for managing breast cancer?

The treatment of breast cancer depends on how far advanced the cancer is (Stage 0-IV) and what type of cancer is present.

Patients with the non-invasive Stage 0 disease are treated with breast breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy. Radiotherapy is given after breast-conserving surgery but is not usually needed. Most patients with estrogen receptor (ER) positive cancer will be given endocrine therapy (tamoxifen, anastrozole, raloxifene) post-operatively to decrease the risk of recurrence (the cancer coming back), as well as prevention of new cancers in both the remaining and contralateral breast.

For patients with early and advanced stages of invasive breast cancer, the treatment approach will include surgery plus radiotherapy. Most patients will then receive adjuvant therapy with one or a combination of systemic treatments, such as:

- In early-stage breast cancer - epirubicin / docetaxel / tamoxifen (ER) / trastuzumab (HER2);

- In advanced breast cancer – additional therapy with targeted therapies - palbociclib in ER-positive tumors, lapatinib in HER2-positive, and olaparib in BRCA-associated breast cancer.

Prognosis

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

According to the National Institute of Health Statistics Center [cancer.gov], new female breast cancer cases have been rising on average by 1.0% each year over 2012-2021. Nevertheless, age-adjusted death rates have been falling on average 1,2% each year over 2013-2022. Moreover, 5-year relative survival trend has steadily risen from 76% in 1980 to 93% in 2022.

The more early the breast cancer was diagnosed, the better survival chances were observed in the patients. Thus, 99.6% of patients from the early (localized) breast cancer group, 86.7% - from the locally advanced (regional) breast cancer group, and 31.9% - from metastatic (distant) breast cancer group are five-year survivors after the initial diagnosis and treatment.

Regular follow-up is required after the therapy, meaning mammography every year and physical examination every 3-4 months for the first two years after treatment, then every 6-8 months from years 3-5 and once a year thereafter.

Early-stages breast cancer: Diagnostic & treatment management

Algorithm of diagnosis

What evaluations do patients with early-stage breast cancer undergo to identify the best treatment strategy?

Breast cancer in the earliest stages may have a non-invasive (stage 0) or early localized invasive nature (Stages I-IIA). If the margins (edges) of the tumor are limited to the ducts (tubes that carry milk to the nipple) or lobules (glands that make milk), the diagnosis is non-invasive Stage 0 breast cancer or carcinoma in situ. If the tumor cells spread to nearby breast tissue, it is called Stage IA breast cancer. If the tumor cells invade the regional lymph nodes with a lesion size of 0.2-2 mm, it is called Stage IB. In stage IIA, cancer spreads to 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes and organizes the lesions there 0.2-2 mm in size, or the primary breast tumor does not invade the lymph nodes but has a size of 20-50 mm.

The diagnostic interventions include clinical examination, imaging, and biopsy.

- Clinical examination of the breasts and lymph nodes. Additionally, the doctor collects information about any family history of breast cancer and whether the patient reached menopause or not. This step may also include a blood sample for routine blood tests and further continue to arrange an imaging scan if a suspicion of having a breast tumor arises.

- Imaging techniques, such as mammography, ultrasound, and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan:

- Mammography is a type of low-dose x-ray that looks for early breast cancers. Breasts are placed on the x-ray machine and pressed between two plates to produce a clear image. If the mammography screening shows any suspicious lesions or shadows in the tissue, there is a signal for the physician to investigate further.

- Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to create an image of the inside of a patient’s body. In investigations for breast cancer, a hand-held ultrasound device lets the doctor examine the breasts and the lymph nodes in the patient’s armpit. The ultrasound can show whether a lump is solid or a fluid-filled cyst, sometimes indicating a benign lesion (non-cancer origin).

- MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of the inside of a patient’s body. An MRI scanner is usually a large tube that contains powerful magnets. The patient lies inside the tube during the scan, which takes 15–90 minutes. Although these are not used as part of routine investigations, an MRI scan might be used in certain circumstances, for example, in patients with a family history of breast cancer, BRCA mutations, breast implants, or lobular cancers, if there is a suspicion of multiple tumors, or if the results of other imaging techniques are inconclusive [Loibl et al., 2024]. MRI is also used to see if a cancer has responded to treatment and to plan further therapy.

- The biopsy is taken with a needle, usually guided by ultrasound (or sometimes using mammography or MRI if the tumor is not visible on ultrasound) to make sure the biopsy is taken from the correct area in the breast. The biopsy gives the doctors important information on the type of breast cancer. At the same time as the biopsy, a marker may be placed into the tumor to help surgeons remove the whole tumor at a later date. Different types of biopsies are classified by the technique and/or needle size used to collect the tissue sample.

- Fine needle aspiration biopsy – uses a thin needle to remove a small cell sample.

- Core needle biopsy – utilizes a wider needle to collect a large tissue sample, which is usually preferable to perform cancer biomarker tests for investigation a hormone receptor status (estrogen receptor – ER, progesterone receptor – PgR) and Human Epidermal Growth Factor 2 (HER2) gene expression status to guide treatment options. Due to the larger needle, local anesthesia (pain blockade in the breast) is used during the procedure.

- A sentinel lymph node biopsy is used if the cancer spreads out of the primary location. This kind of biopsy is usually done by surgical intervention when the doctor removes 1 to 3 or more lymph nodes from under the arm that receives lymph drainage from the breast.

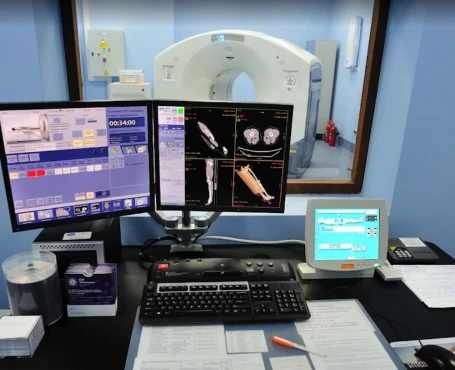

According to the European Society for Medical Oncology’s current clinical guideline, the diagnosis and staging of early-stage breast cancer (EBC) is a sequence of interventions when, on the first step, the diagnosis is confirmed by a bilateral mammogram and ultrasound of both breasts and regional lymph nodes. During the second step, the tissue from the biopsy sample undergoes biomarkers panel analysis in a pathology lab where testing for ER, PgR, HER2, and gBRCA1/2 is performed to investigate the best upcoming treatment strategy. Diagnosis takes minimum blood work-up, such as complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, alkaline phosphatase, and calcium levels. To exclude advanced stages of breast cancer, a computer tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdominal imaging (ultrasound, CT, or MRI scan), and a bone scan are provided for patients with affected axillary nodes, large tumors >50 mm, and metastatic suspicion due to aggressive biology of poorly differentiated / high-grade tumor (when the cancerous tissue looks very different from healthy tissue)

Treatment routes

What is an appropriate treatment for stages 0-IIA breast cancer?

Stage 0 – carcinoma in situ – non-invasive breast cancer treatment

The primary treatment for non-invasive breast cancer is the surgical removal of the tumor. The aim of surgery for early non-invasive breast cancer is to remove the tumor and confirm that it is non-invasive. The surgical team will ensure that the cancer is taken away along with a healthy margin of tissue to help stop it from coming back. Non-invasive breast cancer may be treated with mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery [ESMO, 2024]. Immediate breast reconstruction should be available to women undergoing a mastectomy unless there is a clinical reason not to, such as on-site infection of the chest. Breast reconstruction can make it easier to accept losing a breast and does not affect the ability of doctors to detect any recurrences of the cancer. In general, silicone gel implants are safe, but there is a slight risk (1/30,000 cases) of breast implant implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) [Cardoso et al., 2019].

Radiotherapy – whole-body radiotherapy (WBRT) – is used after breast-conserving surgery. However, there is no need for WBRT after mastectomy with successful removal of a non-invasive cancer.

Systemic therapy, such as tamoxifen, is recommended in ER-positive Stage 0 breast cancer in high-risk patients (with family history of breast cancers of hereditary oncology syndromes).

Stage I-IIA – invasive early (localized) breast cancer treatment

The breast-conserving or mastectomy surgical approach combined with subsequent radiotherapy (WBRT in high-risk or Accelerated partial breast irradiation – APBI – in low-risk patients) and systemic treatment is eligible as first-line treatment for all forms of localized breast cancer if the tumor did not reach lymph nodes. This group includes patients with ER-positive, PgR-positive, HER2-positive, and triple-negative breast cancers.

For the EBC with invaded lymph nodes, neoadjuvant therapy before surgery to shrink a large tumor and reduce the risk of recurrence [cancer.net]. The neoadjuvant systemic options by type of EBC may include:

- For triple-negative breast cancer (tumor size > 10 mm), chemotherapy (carboplatin) and the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab are recommended;

- For HER2-negative, ER/PgR-positive breast cancer – chemotherapy (carboplatin) plus in postmenopausal patients – tamoxifen (or aromatase inhibitors anastrozole / letrozole) to reduce the size of the tumor [Lancet Oncology, 2022];

- For HER2-positive breast cancer (>20 mm in size), chemotherapy (carboplatin) is used in combination with the targeted therapy (trastuzumab/ pertuzumab), but only in the framework of a clinical trial.

Most patients with early invasive breast cancer will receive systemic (adjuvant) therapy after surgery. Adjuvant treatment usually starts between 2 and 6 weeks after surgery, and several types of therapy may be used:

- endocrine therapy in ER-positive EBC: tamoxifen for five years with switching to anastrozole later;

- chemotherapy (docetaxel / doxorubicin) in triple-negative, HER2-positive, and high-risk HER2-negative tumors;

- targeted immunotherapy (trastuzumab / pertizumab) for HER2-positive EBC and pembrolizumab for triple-negative EBC.

Follow-up & surveillance strategy

How do you make sure the EBC will not return?

Annual mammography and physical exams are recommended surveillance strategies for people who have been treated for curable breast cancer. More intensive follow-up in people with no symptoms has not been proven to improve outcomes.

Follow-up care is also vital for screening for other types of cancer. In some instances, patients may be able to visit a survivorship clinic that specializes in the post-treatment needs of people diagnosed with breast cancer.

Advanced breast cancer: Diagnostic & treatment management

Algorithm of diagnosis

What evaluations do patients with advanced breast cancer undergo to identify the best treatment strategy?

Although breast cancer mortality worldwide has been declining over the last thirty years, there are significant differences between five-year survival probability for women diagnosed with early breast cancer (EBC, 96%) and with advanced breast cancer (ABC, 38%) [ESMO, 2021].

The diagnosis of advanced breast cancer includes a group of locally distributed large (< 50 mm) with spreading to axillary lymph nodes – stage IIB if the lymph nodes are movable, stage IIIA if the nodes are fixed or matted, or stage IIIC if the tumor invasion is not limited to the armpit region, but involves internal mammary or supraclavicular (on the neck) lymph nodes. The terminal subgroup of the advanced tumors is metastatic breast cancer (MBC), which produces pathological lesions in other areas of the body.

The advanced breast cancer after therapy for EBC tends to have a more aggressive nature and a worse outcome compared with de novo MBC.

A standard diagnostic work-up protocol includes a core needle biopsy of the metastatic lesion following lab analysis for the key biomarkers ER, PgR, and HER2. After this step, all patients are divided into three groups according to the presence of additional markers that aim to line up the most specific advanced therapy:

- Patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) with the cancer cell markers responsible for the tumor survival.

- Patients with ER-positive / HER2-negative tumors and markers of survival & cellular aggression.

- Other patients who are undergoing the groups (1) and (2) staging protocol via CT of the chest and abdomen, bone scan (or Positron Emission Tomography or PET-CT), and brain imaging (MRI) for symptomatic patients.

An FDG PET/CT uses a radiotracer called F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). It is made of fluoride and a simple form of sugar called glucose. This scan is most helpful when other imaging results are unclear. It may help find cancer lesions in lymph nodes and distant sites. If it clearly shows cancer in the bone, a bone scan may not be needed.

Treatment routes

What is an appropriate treatment for stage IIB-IV breast cancer?

Locally-advanced breast cancer (stage IIB-III)

In most cases, a combination of systemic therapy, surgery, and radiotherapy is used.

The initial treatment for locally advanced breast cancer is usually neoadjuvant systemic therapy to shrink the tumor and improve the likelihood of successful surgical removal of the cancer with a clear margin. In general, the systemic therapies used for early breast cancer are also used for locally advanced breast cancer, although in the advanced disease, systemic treatment is usually given first, patients generally require radiotherapy, and overall, the treatment is more aggressive. Thus, in different types of inoperable locally advanced breast cancer, the following types of neoadjuvant therapy may be considered:

- ER-positive breast cancer – endocrine therapy (anastrozole) OR docetaxel chemotherapy plus tamoxifen;

- HER2-positive breast cancer – docetaxel chemotherapy sequentially with tamoxifen and anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab / neratinib);

- Triple-negative breast cancer – docetaxel and tamoxifen therapy combined.

Patients with locally advanced breast cancer may also receive whole-body radiotherapy (WBRT) as a neoadjuvant treatment. Following effective neoadjuvant systemic therapy, surgical resection of the tumor is often possible. In most cases, surgery will involve a mastectomy and removal of the axillary lymph nodes, but breast-conserving surgery might be possible in some patients. Locally advanced breast cancer is usually treated with systemic therapy, after which surgery may be possible to remove the tumor.

Metastatic breast cancer (stage IV)

Systemic therapy for advanced disease aims to prolong life and maximize quality of life. This result is most effectively achieved with targeted therapies, typically used as the primary treatment in most patients. The targeted therapies, depending on the hormone receptors, HER2 gene, and other BC oncogenes (BRCA1/2) statuses, are arranged according to the mechanism of action:

- Anti-HER2 agents act on the HER2 receptor to block signaling and reduce cell proliferation in HER2-positive breast cancers. Trastuzumab, lapatinib, pertuzumab, and trastuzumab emtansine (TDM-1) are all currently used anti-HER2 agents. Neratinib is a new anti-HER2 agent that may also treat HER2-positive disease.

- Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 (CDK4/6) reduce cellular proliferation in tumors. Palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib are CDK4/6 inhibitors used in the treatment of breast cancer.

- Inhibitors of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), such as everolimus, reduce the growth and proliferation of tumor cells stimulated by mTOR signaling.

- Inhibitors of poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) make it difficult for cancer cells to fix damaged DNA, which can cause cancer cells to die. Olaparib and talazoparib are new PARP inhibitors that may be used to treat some patients with a BRCA mutation.

- Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors, such as bevacizumab, stop tumors from stimulating blood vessel growth within the tumor, thereby starving them of the oxygen and nutrients they need to continue growing.

- Endocrine therapies aim to reduce the effects of estrogen in ER-positive breast cancers. This feature is the most essential type of systemic treatment for ER-positive tumors, also called hormone-dependent tumors. There are several types of endocrine therapy available, which are taken orally or administered as an injection:

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) block ER on breast cells to prevent estrogen attaching to the receptors. Tamoxifen is a type of SERM.

- Selective estrogen receptor downregulators (SERDs), such as fulvestrant, work similarly to SERMs but also reduce the number of ERs.

- Ovarian function suppression by gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs or by surgery may be offered to pre- and perimenopausal women to reduce the supply of estrogen from the ovaries to the tumor.

- Aromatase inhibitors reduce estrogen production in tissues and organs other than the ovaries. They are, therefore, effective only in postmenopausal women unless the function of the ovaries is suppressed (estrogen levels are artificially lowered) in premenopausal women. Anastrozole, letrozole and exemestane are all aromatase inhibitors.

Among other system therapies, patients with bone metastases receive bone-modifying drugs, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab, in combination with calcium and vitamin D supplements. These agents strengthen the bone, reducing bone pain and the risk of fractures.

Metastatic breast cancer is not curable but can be treated with an increasing choice of systemic therapies, which may include:

- Chemotherapy is the standard treatment for triple-negative breast cancer and ER-positive, HER2-negative patients who have stopped responding to endocrine therapy. Occasionally, ER-positive patients may require chemotherapy because the cancer is particularly aggressive. Chemotherapies are usually given sequentially for metastatic disease but may be offered in combination if the cancer is progressing quickly. Patients are typically treated with capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin. Taxanes or anthracyclines may be used again if given before as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy if the patient is considered ‘disease-free’ for at least one year and the doctor considers it safe. Other chemotherapy choices might be preferable due to the tumor’s receptor status. Platinum-containing chemotherapy, such as carboplatin or cisplatin, might also be used in patients with triple-negative disease who have been treated with anthracyclines previously. Everolimus, in combination with exemestane, tamoxifen, or fulvestrant, is a treatment option for some postmenopausal patients with ER-positive advanced breast cancer that has progressed after treatment with a non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor

- Endocrine therapy: ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced disease should almost always be initially treated with endocrine therapy: an aromatase inhibitor, tamoxifen, or fulvestrant (Cardoso et al. 2018). In pre- and perimenopausal patients, ovarian function suppression or ablation (surgical removal) is recommended in combination with endocrine therapy. Where available, endocrine therapy is usually combined with targeted therapies such as palbociclib, ribociclib, abemaciclib, or everolimus to improve outcomes. Megestrol acetate and estradiol (a type of estrogen) are options for further lines of treatment. Patients with ER-positive, HER2-positive metastatic disease will typically be treated with anti-HER2 therapy and chemotherapy as first-line treatment, then may receive endocrine therapy in combination with further anti-HER2 therapy as maintenance treatment after completing chemotherapy.

- Anti-HER2 therapy: The first-line treatment for HER2-positive advanced disease is likely trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with chemotherapy (usually docetaxel or paclitaxel) (Cardoso et al. 2018). The second-line treatment in these patients is typically T-DM1. Some patients may also receive second-line therapy with trastuzumab in combination with lapatinib. Further treatment lines may include combinations of trastuzumab with other chemotherapy drugs or a combination of lapatinib and capecitabine.

- The new agents, olaparib and talazoparib, are PARP inhibitors that may be used as an alternative to chemotherapy in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations.