Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, originates in the stomach, which is part of the digestive system. The stomach is connected to the esophagus at the top and the duodenum at the bottom, and it produces gastric juice that breaks down food for the body to absorb. The stomach has multiple layers, including the inner lining, supportive tissue, and muscle layers.

Most stomach cancers, around 95%, begin in the gland cells of the inner stomach lining and are called adenocarcinomas. Rarer types of stomach cancer include squamous cell carcinoma, which develops in the flat cells lining the stomach, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, a rare type of sarcoma.

Stomach cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide, with over 1 million new cases and 770,000 deaths in 2020. The highest rates are in Eastern Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and South America. Stomach cancer is more prevalent in older adults, with about half of cases occurring in people aged 75 and older, and it is twice as common in men as in women [Annals of Oncology, 2022].

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of stomach cancer?

Several risk factors have been identified for developing stomach cancer. It is essential to understand that having a risk factor increases the likelihood of developing cancer but does not guarantee that a person will get cancer. Similarly, not having a risk factor does not mean someone will not develop cancer.

One of the primary risk factors for stomach cancer is infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria. H. pylori lives in the stomach lining and spreads through contaminated food and water. While H. pylori infection does not cause problems for most people, it can lead to stomach inflammation and ulcers, which may eventually progress to cancer. H. pylori infection is less common in developed countries but remains prevalent in developing regions.

The risk of developing stomach cancer can be reduced by limiting exposure to risk factors, such as reducing alcohol consumption, quitting smoking, and maintaining a healthy diet. Treating H. pylori infection with antibiotics also lowers the risk of stomach cancer.

Approximately 3% of stomach cancers are hereditary, meaning genetic changes cause them to be passed down from parents to their children. Certain hereditary syndromes can increase the risk of stomach cancer. Individuals with a family history of stomach cancer should consult their healthcare provider, as they may be eligible for genetic counseling. Some people at high risk may be offered regular endoscopic surveillance to detect any early signs of cancer.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting stomach cancer?

Stomach cancer frequently goes unrecognized in its early stages because its symptoms are not specific. Common signs include persistent digestive problems and heartburn, loss of appetite and unintended weight loss, abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting, trouble swallowing, and feeling full after eating just small amounts of food.

Diagnostic Route [Cancer Research Journal, 2022]

When, where, and how should the stomach cancer be detected?

The diagnostic process for stomach cancer typically involves several key steps:

- Physical examination to check for any signs of abdominal swelling or tenderness.

- An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy allows one to visualize the stomach lining and collect biopsy samples directly.

- Microscopic examination of the biopsy samples confirms the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, the most common type of stomach cancer.

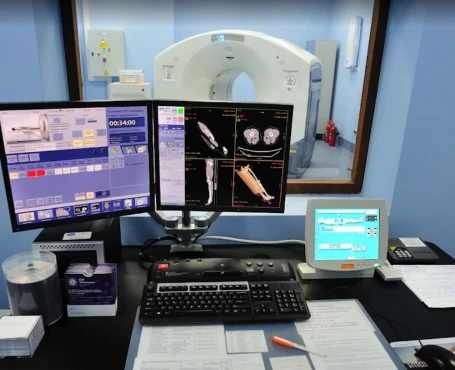

- Imaging studies - CT scans, PET scans, and endoscopic ultrasound - help determine the cancer's extent and spread, guiding treatment planning.

- Staging: the TNM staging system assesses the tumor size, lymph node involvement, and whether the cancer has metastasized to other body parts.

Additional techniques used to assess stomach cancer include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and laparoscopy. EUS is similar to an endoscopy, but the endoscope also has an ultrasound probe that creates images of the internal organs. Laparoscopy is a minor surgical procedure where a thin tube with a light and camera is inserted through a small incision in the abdomen, allowing the doctor to examine the stomach and collect biopsies.

The results of biopsies and imaging scans will determine the type of stomach cancer and how far it has spread. Based on these findings, the doctor will categorize the cancer as:

- Early-stage stomach cancer is confined to the original location and has not spread elsewhere

- Locally advanced stomach cancer has spread to nearby areas and may have affected nearby lymph nodes

- The metastatic stage has spread the tumor to another part of the body, with the lesions in locations away from the original cancer site.

Biopsies taken during the endoscopic procedure may also undergo molecular testing or additional biopsies may be collected for molecular testing at a later time, usually if the cancer has spread. This type of testing can identify specific biological markers (biomarkers) in the cancer cells, which can help determine the best treatment.

Suppose molecular testing shows that metastatic stomach cancer has a high level of the biomarkers human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Specific treatments for those types of stomach cancers (HER2-positive or PD-L1-positive disease) may be offered in that case. Suppose the tumor is found to have a high number of mutations within microsatellites (short, repeated DNA sequences) or changes in particular genes involved in correcting DNA copying mistakes. In that case, it has microsatellite instability-high (MSI-high) or mismatch repair-deficient (MMR-deficient) cancer, which will influence the treatment.

Biomarker research is evolving quickly, and other biomarkers to guide treatment may soon become available (e.g., fibroblast growth factor receptor two and claudin-18.2). However, it's essential to understand that molecular testing and biomarker-based treatment are not available in all countries.

Treatment Approaches [American Cancer Society, 2024]

What are the options for managing stomach cancer?

Surgical treatment methods

The goal of surgical resection is to remove the cancer along with a healthy margin of tissue around the tumor to help prevent it from returning. However, it's important to understand that not all stomach cancers can be treated with surgery; it is generally not recommended for patients with metastatic disease. The type of surgical resection depends on the stage of the tumor, with a response rate of 60-70% in a 5-year survival period in localized stomach cancer.

Surgical options for stomach cancer include:

• Endoscopic resection, where the tumor is removed from the lining of the stomach using an endoscope. This type of surgery is typically only used to remove early-stage stomach cancer.

• Gastrectomy, where the entire stomach (radical gastrectomy) or a part of the stomach (partial gastrectomy) is removed.

During a gastrectomy, nearby lymph nodes are also removed. This ensures the cancer is entirely removed with a healthy margin. After a gastrectomy, the surgeon must remodel the digestive system. After a partial gastrectomy, the duodenum is joined to the remaining part of the stomach. At the same time, the duodenum is joined to the esophagus if a radical gastrectomy is applied.

Chemotherapy is used to destroy cancer cells and is employed in the treatment of both early-stage and advanced stomach cancer. In some cases, chemotherapy may be combined with radiotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves 5-year survival rates in early-stage stomach cancer by about 10%.

Chemotherapy can be given as a single agent or in combination with other drugs; for instance, FLOT is a combination of 5-FU, folinic acid, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel used to treat stomach cancer. In advanced-stages gastric adenocarcinoma, chemotherapy achieves response rates of 30-50%, extending median survival to 10-12 months.

It's important to understand that not all chemotherapy agents suit every patient. Some patients may be unable to tolerate specific chemotherapy regimens due to their overall health and fitness level.

Before receiving certain chemotherapies (including 5-FU and capecitabine), a test may be performed to check for a deficiency in an enzyme called dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase. If a deficiency is found, the chemotherapy dose may be lowered, or a different type of chemotherapy may be selected instead.

Radiotherapy uses ionizing radiation to damage the DNA of cancer cells, causing them to die. In treating stomach cancer, radiotherapy is often combined with chemotherapy.

Targeted therapies are drugs that block specific biological processes in cancer cells that encourage them to grow. Ramucirumab is a monoclonal antibody that attaches to a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2). By blocking VEGFR2, ramucirumab stops the cancer from developing the blood vessels it needs to grow. Trastuzumab is another monoclonal antibody that attaches to HER2 in cancer cells and kills them. This treatment has also been combined with a chemotherapy agent to produce trastuzumab deruxtecan. Trastuzumab and trastuzumab deruxtecan are only used when molecular testing shows the cancer is HER2 positive (see 'Molecular tests' for more information). Ramucirumab, trastuzumab, and trastuzumab deruxtecan are used to treat metastatic stomach cancer and are given intravenously.

Immunotherapies are treatments that block processes that reduce the body's immune response to cancer. They help reactivate the immune system to detect and fight the cancer. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are intravenous immunotherapies that block the actions of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1). PD-1 suppresses the immune response to cancer, but when its actions are blocked by immunotherapy, the immune system is reactivated to fight the cancer. Nivolumab is used when molecular testing shows the cancer is PD-L1-positive, and pembrolizumab is used for MSI-high/MMR-deficient tumors and for PD-L1-positive tumors at the junction where the stomach meets the esophagus.

Prognosis & Follow-up

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with stomach cancer?

The prognosis for stomach cancer is closely tied to the stage when it is detected. Those diagnosed with early-stage stomach cancer generally have a favorable prognosis, with 5-year survival rates between 60% and 70%. However, advanced-stage stomach cancer has a less favorable outlook, with 5-year survival rates falling to around 5% to 20% due to the higher risk of the cancer spreading and recurring.

Regular follow-up care is crucial for monitoring potential cancer recurrence and managing any long-term side effects of the treatment. The typical follow-up schedule involves frequent visits in the first few years, gradually tapering off to annual checkups. Patients typically see their healthcare team every 3 to 6 months in the first year after treatment. The visits occur every 6 to 12 months during the second to fifth year. After the initial five years, annual follow-up appointments are recommended. These visits usually include a physical exam, endoscopy, and imaging tests as needed to check for any signs of the cancer returning. Additionally, long-term follow-up care focuses on managing persistent side effects, such as nutritional deficiencies or gastrointestinal complications, to ensure the patient's overall well-being.