Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Ovarian cancer and fallopian tube cancer, while relatively uncommon, are highly lethal gynecologic malignancies. According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 19,680 women in the United States are expected to receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 2024, and it is the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths among women in the United States. There are about 250,000 women in the US living with ovarian cancer and FTC [NCI, 2024].

Ovarian cancer can be categorized based on the type of cells where the cancer starts:

- Epithelial tumors represent about 90% of ovarian cancers. These lesions originate from the ovary's surface layer (epithelium) or the fallopian tube.

- Germ cell tumors are less common and typically affect younger women. They develop from the cells that produce eggs.

- Stromal tumors are rare and arise from the connective tissue cells within the ovary, which are responsible for producing the female hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Ovarian cancer is the seventh most common cancer in women worldwide and predominantly affects older, postmenopausal women over 50.

Epithelial ovarian tumors are prevalent in this disease, as they grow from the most common cells in women's reproductive system – ovarian epithelium, a thin layer of cells covering the ovary - or from the fallopian tube epithelium.

The four main histological subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer are as follows:

- Serous carcinoma accounts for around 80% of advanced cases. These cancer subtype can be further divided into high-grade and low-grade varieties, with low-grade tumors comprising roughly 10% of serous carcinomas. Low-grade serous tumors tend to affect younger women and have a better prognosis.

- Mucinous ovarian cancers make up 7-14% of primary epithelial cases. If caught early, this subtype has an excellent prognosis.

- Endometrioid ovarian cancers occur in around 10% of patients and are typically low-grade, early-stage tumors with favorable prognosis.

- Clear-cell ovarian cancers affect about 5% of patients, though the proportion can vary by region. This subtype also has a relatively good prognosis when diagnosed early.

Fallopian tube cancer is relatively uncommon, accounting for only a tiny segment of gynecologic malignancies. It is frequently detected incidentally during surgical procedures or other gynecologic health issues.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of ovarian & fallopian tube cancer?

The precise cause of ovarian cancer remains unknown, but several risk factors have been identified that can increase the chances of developing the disease. It's essential to keep in mind that the presence of risk factors does not necessarily mean a person will get cancer. Similarly, the absence of risk factors does not guarantee protection against the disease.

Factors that increase the risk of ovarian cancer and FTC:

- Age. The risk increases as one age, with most cases occurring in women over 50.

- Reproductive history in women who have not had children, experienced infertility issues, or had their first child after age 30 have a higher risk association.

- Early start of menstruation and late menopause

- Obesity due to higher body mass index has been linked to an increased risk.

- Family history. Women with a close relative who had cancer are at more than double the risk of developing ovarian cancer compared to those with no such family history. Women with hereditary ovarian cancer tend to develop the disease around ten years earlier than those with non-hereditary ovarian cancer.

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Approximately 6%-25% of ovarian cancers have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, with these mutations most frequently seen in high-grade serous tumors. Inheriting a BRCA1 mutation increases the risk of developing ovarian cancer by 15%–45%, while inheriting a BRCA2 mutation increases the risk by 10%–20%. Those who test positive for a BRCA1/2 mutation will be monitored closely and offered risk-reduction measures. Due to the early onset of ovarian cancer in women carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, as well as the difficulties of detecting it in its early stages, women over 25 with a family history of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation should undergo testing or at least regular monitoring. Women found to have a high-grade tumor at surgery should also be tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation.

Certain factors may help reduce the risk of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers. For instance, using oral contraceptive pills has been shown to lower the chances of developing these cancers, perhaps by suppressing ovulation. Additionally, procedures like female sterilization, where the fallopian tubes are blocked or removed, can also decrease the risk. Breastfeeding has also been associated with a lower incidence of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers, though the exact mechanisms are not fully understood [National Cancer Institute, 2023].

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting ovarian & fallopian tube cancer?

The symptoms of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers are often subtle and general, which can delay diagnosis. Some common signs include abdominal or pelvic discomfort, irregular vaginal bleeding, changes in bowel habits like constipation or diarrhea, a swollen abdomen, fatigue, and a frequent need to urinate. These nonspecific symptoms can easily be mistaken for more benign conditions, highlighting the importance of prompt medical evaluation for anyone experiencing persistent or concerning changes in their health.

In advanced cases of ovarian cancer and fallopian tube cancer, patients may experience additional concerning symptoms. These can include a noticeable increase in abdominal size, a feeling of bloating, nausea, loss of appetite, indigestion, a sense of fullness even after just starting to eat, and difficulty breathing. These more pronounced symptoms often arise as the disease progresses, highlighting the importance of prompt medical attention for anyone experiencing persistent or worsening abdominal or pelvic discomfort.

Algorithm of diagnosis

What evaluations do ovarian cancer and FTC patients undergo to identify the best treatment strategy?

Unless a woman is already being monitored because the patient has tested positive for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, she is most likely to be diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer or FTC because early disease typically has no symptoms. The patient may have noticed bloating and abdominal discomfort or, in some cases, may become aware of swollen lymph nodes in her groin, armpits, or neck just above the collarbone.

A diagnosis of ovarian cancer or FTC is based on the results of the following examinations and tests:

- Clinical examination. The abdomen will be examined, and the lymph nodes will be checked for enlargement. If there is a suspicion of epithelial ovarian cancer, a blood test and/or abdominal ultrasound scan may be arranged, and a referral to a specialist for further testing may be made. The blood test will measure a substance called CA-125, which is raised in about 50% of women with early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer and about 85% of those with advanced disease. CA-125 is not specific to epithelial ovarian cancer; it can be higher than average in people with various other types of cancer and also in women with non-malignant gynecological conditions. Because of this, it must be considered alongside other tests before a diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer can be made.

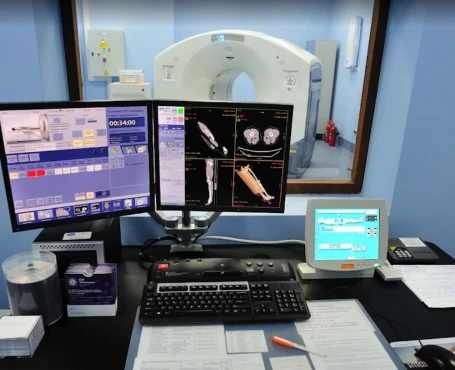

- Imaging studies. Typically, the first imaging test performed when epithelial ovarian cancer is suspected is an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis. This scan, done with a special instrument inserted into the vagina, allows the medical team to examine the size, shape, and other characteristics of the ovaries that are associated with this type of cancer.

Additionally, a computed tomography (CT) scan, a type of three-dimensional x-ray, can be used to determine the extent of the cancer and plan any necessary surgery. This painless procedure takes around 10-30 minutes.

An alternative to the CT scan is a chest x-ray, which the specialist can use to check for any spread of the cancer to the lungs and chest cavity.

Although not part of routine investigations, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan can also be used instead of a CT scan to plan surgery. The MRI uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of the inside of the body. The patient lies inside a large, tube-like MRI scanner during this 15-90 minute procedure.

Ovarian cancer and FTC staging

Ovarian cancer is staged using the FIGO system, which examines the size, location, and spread of the tumor. This staging is typically done during surgery, as the full extent of the cancer is often not known until tissue samples are removed and analyzed.

The FIGO staging system has four main stages, with lower stages indicating a better prognosis. Staging considers the tumor size, whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes, and if it has metastasized to distant sites.

Before surgery, imaging tests like CT or MRI scans are crucial to help the surgeon plan the procedure. During the operation, tumor samples are collected and sent for further testing to determine the specific subtype of epithelial ovarian cancer.

Treatment routes

What is an appropriate treatment for different ovarian cancer and FTC stages?

General principle

For women whose cancer is still confined to the ovaries or fallopian tubes or has advanced only locally, surgery is the primary form of treatment – with or without chemotherapy. Those with advanced disease may also, in certain circumstances, benefit from surgery, and they will receive some form of chemotherapy afterward. If the cancer relapses after treatment, it will be managed with chemotherapy (possibly together with targeted therapy) to slow its growth and relieve symptoms [NIH, 2023].

Surgery

The aim of surgical management for early ovarian cancer or FTC is to remove the tumor and establish the disease stage; this will help decide if chemotherapy is needed. The surgeon will remove the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus, as well as any affected lymph nodes. Sometimes, other tissues close to the tumor location will also be removed. This ensures that as much of the cancer as possible is removed, along with a healthy ‘margin’ of tissues to help stop its return. For a younger woman who has not yet completed or had a family, fertility-sparing surgery may be possible, but this depends on the precise nature of the epithelial ovarian cancer and any potential risks will be discussed.

Chemotherapy

Women with Stage I disease who are considered to be at intermediate or high risk of their cancer recurrence will quite often be given chemotherapy after their surgery – usually after they have had time to recover from the procedure. The treatment supported by the most robust evidence is with single-agent carboplatin.

All women whose ovarian cancer or FTC has been classed as Stages II, III, or IV should receive chemotherapy after surgery if their cancer is operable. The standard treatment is with a regimen of two drugs – paclitaxel and carboplatin – both given intravenously once every three weeks (with each round of treatment called a ‘cycle’). Usually, six cycles of treatment are given. For women who develop an allergy to paclitaxel or cannot tolerate it, docetaxel or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin can be substituted and given with carboplatin.

Targeted therapy

There is currently only one targeted drug that has been licensed in Europe for first-line treatment of ovarian cancer. This is called bevacizumab, a drug that stops a tumor from stimulating blood vessel growth and so ‘starves’ it of the nutrients it needs to continue growing. It is licensed in Europe in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin for front-line treatment of women with Stage III B, III C, or IV epithelial ovarian cancer.

Another targeted drug that acts differently from bevacizumab is olaparib, which inhibits an enzyme called PARP that a tumor needs to repair its DNA and continue growing. Olaparib has been licensed in Europe as a single agent for the maintenance treatment of women with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, high-grade, serous epithelial ovarian cancer that has tested positive for BRCA1 mutation or BRCA 2 mutation who have responded entirely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy. Individuals who meet these criteria may be offered treatment with olaparib to help maintain the response to chemotherapy for as long as possible. Unlike many other drugs used to treat ovarian cancer or FTC, olaparib comes in capsule form and is taken orally.

Niraparib is another drug that inhibits the PARP enzyme. In Europe, it has recently been recommended for use as maintenance treatment in adult women with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, high-grade, serous epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who are responding to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA1/2 mutation status. Like olaparib, niraparib also comes in capsule form and is taken orally.

Prognosis & Follow-up

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

The prognosis for ovarian and fallopian tube cancers varies widely depending on the stage at diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate for localized ovarian cancer is about 92%, but only 19% of cases are diagnosed at this early stage. The overall 5-year survival rate for ovarian cancer is approximately 51%.

Regular follow-up is crucial for monitoring for recurrence and managing any long-term side effects of treatment. The typical follow-up schedule includes clinical examinations every 3-4 months for the first two years, then every six months for the next three years, and annually after that. CA-125 blood tests are monitored regularly, especially if elevated before treatment. CT scans or ultrasounds may be used periodically to monitor for recurrence.