Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Cancer cells begin growing elsewhere in the body and then travel to the brain to form metastatic brain tumors. For example, cancers of the lung, breast, colon, and skin (melanoma) frequently spread to the brain via the bloodstream or a magnetic-like attraction to other organs of the body. All metastatic brain tumors are, by definition, malignant and can genuinely be called “secondary brain cancer” or “brain metastases.”

Each year, more than 94,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with a primary brain tumor, and more than twice that number are diagnosed with a metastatic tumor. The incidence of brain metastases appears to be increasing [Amsbaugh & Kim, 2023]. In 2023, this number reached 200,000 patients [braintumor.org].

Almost all kinds of cancer have been associated with the risk of brain metastases. The most common oncology diseases are melanoma, lung, breast, renal, and colorectal cancers [AANS 2024; Redmer 2018; Lamba et al. 2021]. About 10-30% of cancer patients may develop brain metastases during their disease history [hopkinsmedicine.org].

Metastatic brain tumors usually contain the same type of cancer cells found at the primary site. For example, small-cell lung cancer that moves to the brain forms small-cell cancer in the brain. Squamous-cell head and neck cancer forms squamous-cell cancer in the brain. Brain metastasis can present as a single or multiple tumor.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting metastatic brain cancer?

The symptoms of metastatic brain tumors are the same as those of primary brain tumors and are related to the location of the tumor within the brain. Each part of the brain controls specific body functions. Symptoms appear when areas of the brain can no longer function properly. Headache and seizures are the two most common symptoms. Disturbance in the way one thinks and processes thoughts (cognition) is another common symptom of a metastatic brain tumor. Cognitive challenges might include difficulty with memory (especially short-term memory) or personality and behavior changes. Motor problems, such as weakness on one side of the body or an unbalanced walk, can be related to a tumor located in the part of the brain that controls these functions.

Metastatic tumors in the spine may cause back pain, weakness, or changes in sensation in an arm or leg, or may cause loss of bladder/bowel control. Both cognitive and motor problems may also be caused by edema, or swelling, around the tumor.

Diagnostic Route

When, where, and how should secondary brain cancer be detected?

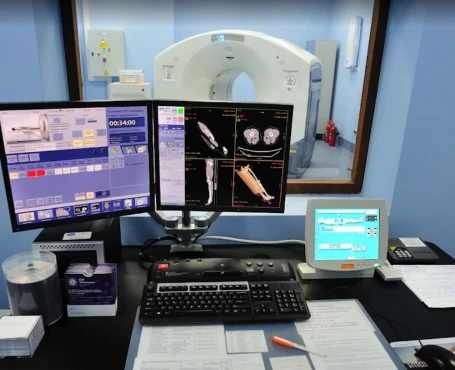

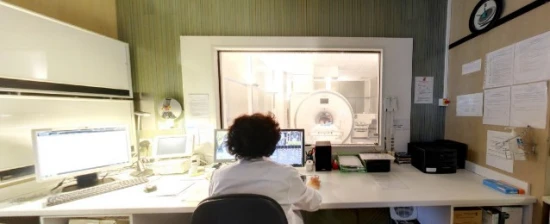

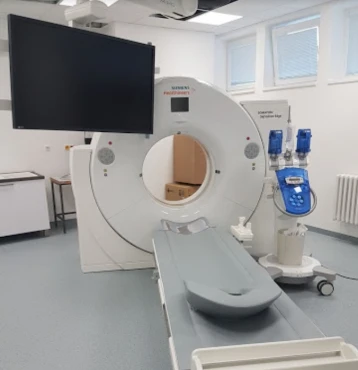

Brain scans such as Computer Tomography (CT scan – fast test), or Magnetic Resonance Tomography (MRI scan – gold standard), and lumbar puncture (spinal tap) are the tools to take a broad picture of the lesion number and metastatic origin of the brain tumor.

The lumbar puncture is used to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample. This procedure is usually avoided if there is any indication of increased intracranial pressure because of the risk of herniation, or the brain’s bulging through an opening in a membrane, muscle, or bone.

The sample of CSF is examined in a laboratory to determine if tumor cells, infection, protein, or blood is present. The presence of tumor cells in the CSF indicates tumor spread. That information is used for tumor staging and helps the doctor determine appropriate treatment choices.

In addition to tumor cells and substances that indicate the presence of a tumor, the CSF may also be examined for the presence of known tumor markers. Some common biomarkers include the following [ESMO Guidelines, 2021]:

- MGMT & EGFRvIII – glioblastoma (primary brain cancer);

- IDH1/IDH2 – primary brain cancer or blood cancer, such as acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes;

- 1p/19q – oligodendroglioma (primary brain cancer);

- EGFR – secondary brain cancer marker associated with non-brain cancer origins of the tumor, such as lung, pancreas, head & neck, liver, or others.

- TERT – secondary brain cancer marker associated with bladder, colorectal, lung, thyroid, head & neck cancer, as well as melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma.

Suppose the MRI brain scan shows a suspected brain tumor. In that case, the next step of a patient is likely to be a consultation with a neurosurgeon, radiation oncologist, or medical/neuro-oncologist. After analyzing the MRI scans, the neurosurgeon determines if the tumor(-s) can be surgically removed or if other treatment options would be more reasonable.

Treatment Approaches

What are the options for managing metastatic brain cancer?

The three main categories of treatments include surgery, radiation (whole brain radiation, stereotactic radiosurgery, or both), and medical therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immune-based therapy). More than one type of treatment might be suggested.

Early treatment of a patient’s brain tumor focuses on controlling symptoms, such as swelling of the brain and/or seizures. If the patient has a limited number of metastatic brain tumors (generally one to three tumors, or a small number of lesions that are close to each other) and if the primary cancer is treatable and under control, the brain metastases’ treatment plan may include surgery to confirm the diagnosis and remove the tumor, followed by a form of radiation therapy (Gamma Knife). This step is generally followed by medical therapy (corticosteroids, anti-seizure medications) that may impact not only the primary cancer but also the metastatic brain tumor.

If there are multiple brain metastases (four or more brain tumors), traditionally hippocampal sparing whole-brain radiation therapy with memantine has been recommended; however, recently, the use of radiosurgery or medical treatment has increased. The stereotactic surgery method is standard for patients with large lesions (one to ten brain tumors) [Yamamoto et al., 2017].

If there is a question about the scan results or the diagnosis, a biopsy or microsurgical resection to remove the brain tumors may be done. This approach allows physicians to confirm that the brain tumors are related to the primary cancer. Metastases to the spine may be treated with radiation therapy alone or with surgery plus radiation.

Prognosis

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

The number of metastases is not the sole predictor of how well the patient might do following treatment. Their neurological function (how the patient is affected by the brain metastases), the status of the primary cancer site (i.e., the presence/absence of metastases in other parts of the body), type of cancer, and the genetic alterations in cancer also appear to influence overall survival. Treatment decisions consider long-term survival possibilities, the patient’s quality of life during and after treatment, and cognition concerns.

Local recurrence following surgical resection, the historical standard in patients with good performance status is 57% in 12 months after the operation [Lancet Oncology, 2017]. Local control might be improved via whole-brain radiotherapy or postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery, giving a patient one year as the median overall survival period [Lancet Oncology, 2018].