Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors are a diverse group of growths that develop from the hormone-producing cells within the digestive tract. These tumors can secrete hormones and are classified based on their location, including the stomach, intestines, pancreas, and rectum.

GI-NETs are relatively uncommon, making up around 2% of all gastrointestinal cancers. However, their incidence has risen in recent decades due to advancements in diagnostic methods and greater awareness. The prevalence is higher because many tumors are slow-growing, leading to longer survival times. GI-NETs are slightly more prevalent in women than men and typically manifest in the fifth or sixth decade of life.

The most prevalent locations for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs) are the small intestine (39%), rectum (15%), appendix (7%), colon (5-7%), and stomach (2-4%). Small bowel GI-NETs are becoming more common and represent the most frequent primary malignancies in the small intestine.

There are several subtypes of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors based on the tumor's location and hormone production ability.

Gastric NETs can be classified into three groups. Type I is associated with chronic inflammation of the stomach lining and high levels of the hormone gastrin. Type II is linked to a syndrome called Zollinger-Ellison and a condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Type III are sporadic tumors not connected to high gastrin levels, and they tend to be more aggressive.

Small intestine NETs are most commonly found in the ileum, the final section of the small intestine. These tumors often go undetected until an advanced stage because their symptoms are nonspecific.

Pancreatic NETs can be divided into two categories. Functional pNETs produce hormones like insulin, gastrin, and glucagon. Non-functional pNETs do not secrete hormones and are usually discovered later on.

Finally, colorectal NETs typically originate in the rectum, with fewer cases arising in the colon. These tumors are generally small and often found unexpectedly during colonoscopy procedures.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of GI NETs?

Although the exact cause of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs) remains unknown, several risk factors have been identified. Genetic syndromes like Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 and Neurofibromatosis type 1 can increase the risk of developing pNETs and duodenal/periampullary NETs, respectively. Additionally, chronic health conditions such as chronic atrophic gastritis and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome have been linked to type I gastric NETs. At the same time, a positive family history of neuroendocrine tumors or other endocrine cancers may also elevate the risk of developing GI-NETs in general.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting GI NETs?

The symptoms of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs) can vary depending on the tumor's location and whether it produces hormones:

- Gastric NETs often present with nonspecific symptoms like abdominal pain, anemia, or gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Small intestine NETs (SI-NETs) may cause abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, or carcinoid syndrome (flushing, diarrhea, wheezing).

- Pancreatic NETs (pNETs):

- Functional pNETs produce hormones, leading to symptoms related to excess hormone secretion (e.g., hypoglycemia from insulinomas).

- Non-functional pNETs typically cause abdominal pain, weight loss, or jaundice.

- Colorectal NETs may result in rectal bleeding changes in bowel habits or be asymptomatic and found incidentally during medical exams.

Diagnostic Route

When, where, and how should the GI NETs be detected?

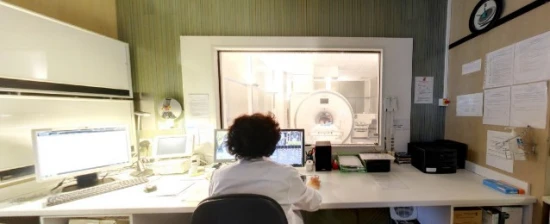

Diagnosing gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs) typically involves a multi-pronged approach. Imaging tests like CT and MRI scans can help locate the primary tumor and check for any metastases. Endoscopic ultrasound is beneficial for evaluating pancreatic NETs. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy can also assist in staging the disease and identifying receptor-positive tumors.

In addition to imaging, biochemical tests play a crucial role. Measuring chromogranin A levels, a marker often elevated in NETs, can provide valuable diagnostic information. Depending on the patient's symptoms and suspected tumor type, specific hormone assays may also be ordered.

Moreover, a histopathological examination, typically through a biopsy, is essential to confirm the diagnosis and gather details about the tumor's grade and level of differentiation.

The grade of a neuroendocrine tumor (NET) is determined by how abnormal the cancer cells and tissue appear under a microscope and how quickly the cancer cells are growing and spreading. A pathologist will analyze the tumor sample to assign a grade.

Generally, lower-grade NETs indicate a better prognosis, while higher-grade cancers tend to grow more quickly and require more intensive treatment.

The World Health Organization classifies NETs and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) based on factors like the amount of cancer present and the tumor's aggressiveness. Critical determinants of NET grade include the Ki-67 index and whether the tumor is well-differentiated or poorly differentiated.

Ki-67 is a protein that reflects cell division and proliferation. Higher levels of Ki-67 in tumor cells suggest they are dividing more rapidly. The Ki-67 index helps establish the tumor grade, indicating how fast the cancer grows.

Low-grade NETs, classified as grade 1 or 2, are well-differentiated tumors with a Ki-67 index below 20%. These are less aggressive cancers. In contrast, high-grade tumors with a Ki-67 over 20% are considered grade 3. Grade 3 NETs can be either well-differentiated or poorly differentiated, with the latter category (poorly differentiated NECs) growing faster, being more aggressive, and requiring different treatment approaches than lower-grade NETs.

Before receiving a GI NET diagnosis, patients see, on average, five healthcare providers during 12 visits. In addition, the median time from the first symptoms to the correct diagnosis of GI NETs is 4.3 years.

Treatment Approaches [ESMO, 2020]

What are the options for managing GI NETs?

Interestingly, around 72% of patients with NET have surgery, and 91% of patients with NET want a more comprehensive range of treatment options for ongoing management of their NETs.

Pancreatic NET location may be managed surgically via:

• Distal pancreatectomy: This procedure removes the body and tail of the pancreas. If the cancer has spread to the spleen, the spleen may also be taken out.

• Central pancreatectomy: This surgery removes the neck and part of the body of the pancreas but leaves the tail intact to help maintain the pancreas's functions.

• Enucleation: This involves removing just the tumor and may be done when the cancer is localized to one area of the pancreas.

• Pancreatoduodenectomy: Also known as the Whipple procedure, this complex surgery removes the head of the pancreas, gallbladder, nearby lymph nodes, part of the stomach and small intestine, and the bile duct. However, enough of the pancreas is left behind to continue producing digestive enzymes and insulin.

Another gastrointestinal tract NET removal tactic depends on the tumor location. It may include an appendectomy (appendix removal), a gastrectomy (partial or complete removal of the stomach), a small bowel resection, and a segmental colon resection (or hemicolectomy).

The surgical approach may destroy cancer cells by:

-

cryosurgery with ultrasound guidance (involves the use of an instrument to freeze and destroy NET tissue);

-

endoscopic resection (the removal of a small tumor from the inner lining of the GI tract, accessed through the mouth and passed down the esophagus to the stomach and sometimes the duodenum).

Different therapies or drugs are used to slow or stop the growth of neuroendocrine cancer cells. Close to half of patients who have a NET report using drug therapies other than chemotherapy, including somatostatin analogs, with a response rate of 50-70% (octreotide, lanreotide). Fewer patients (about 1 in 5) reported being treated with chemotherapy (capecitabine, cisplatin, etoposide) and targeted therapy (sunitinib for advanced pNETs, everolimus, and Lu-177 DOTATATE).

Prognosis & Follow-up

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with GI NETs?

The prognosis for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs) largely depends on the type and stage of the disease. For localized, early-stage, well-differentiated tumors, the 5-year survival rate is around 90%, indicating a favorable prognosis. However, as the cancer spreads regionally, the 5-year survival rate drops to approximately 60-70%. Unfortunately, in cases with distant metastatic disease, the 5-year survival rate falls to around 30%, reflecting the more advanced and aggressive nature of the cancer.

Regular follow-up is crucial for effectively managing gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (GI-NETs). In the initial phase, patients should undergo check-ups every 3 to 6 months, involving physical examinations, monitoring of biochemical markers, and various imaging tests. As the patient progresses through treatment and the disease stabilizes, these follow-up visits can be reduced to every 6 to 12 months, typically after the first 2 to 3 years. The specific schedule may be adjusted based on the individual's disease progression and overall condition.