Colorectal Cancer – The Disease Explanation

Disease types & epidemiology

How common is the disease?

Colorectal or colon cancer is a disease in which cells in the large intestine grow out of control. Regardless of where the cancer started – in the colon or the rectum – tumors in these locations share a lot in common, which is why they’re together known as colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) predominantly develops as malignant tumors where cells are at first dividing on-site and then spreading in different tissues out of the intestine.

The variety of abnormal cells defines the colorectal cancer type. The most common – 95% - are adenocarcinomas, which arise from glandular epithelial cells. Typical adenocarcinoma takes at least ten years to develop from benign adenoma. However, about 15% of adenocarcinomas are more aggressive in two cases: mucinous adenocarcinoma – 10% of CRC – and signet ring cell adenocarcinoma – 1% of CRC. These tumors may spread rapidly within 2-3 years after appearing and are more challenging to treat.

Rare CRC types – less than 1 % of each kind – are:

- neurons-derived carcinoid tumors called Neuroendocrine Tumors (NET);

- lymphocyte-derived Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma;

- intestinal “pacemaker” cells of Cajal produce rare Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST);

- “cancer of smooth muscle in rectum or colon” - Leiomyosarcoma;

- colon and rectal Melanomas from pigmental epithelial cells;

- colorectal squamous cell carcinoma;

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) – a specific inherited condition associated with massive large intestine polyposis from 10-12 years of age.

In the United States, there are 36.6 new cases of CRC per 100,000 men and women per year. According to the National Cancer Institute, about 4.1% of adults will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer at some point in their lifetime.

Causes & risk factors

What is the primary issue of colon cancer?

CRC includes 20-30% hereditary (FAP and Lynch syndrome) and 70-80% spontaneous cases.

The most common scenario for adenocarcinoma CRC development is when epithelial cells undergo a series of genetic or epigenetic changes that enable them to be hyperproliferative – grow fast and spread far. The cancer begins from a tiny benign adenoma in the colorectal segment of the intestine. During the next 10-15 years, under the influence of persistent chronic inflammation from carcinogens and mechanical defects, the adenoma may acquire some cellular damage via pathways of microsatellite instability (MSI) – in 20% of cases - and chromosomal instability (CIN) – 80%.

The cause of CRC is DNA mutations in the inner layer cells of the intestine. Under the influence of genetic damage, bowel epithelium grows uncontrollably. That is a transformation caused by the loss of the tumor suppressor gene APC, which leads tiny adenoma to grow into large but still benign one. Consequently, the activation of KRAS/ BRAF oncogenes and loss of tumor suppressor genes DCC and p53 open a gate of adenoma-to-adenocarcinoma transition through early and late adenoma stages to malignant tumor.

There are two groups of risk factors for the development of CRC: non-modifiable and modifiable. The first group cannot be controlled by individuals, while modifiable risk factors are related to individual habits or lifestyles.

Non-modifiable risk factors for CRC

· Age: most colorectal malignancies manifest at over 50 years. On average, spontaneous colon cancer occurs at 68 years in men and at 72 years in women, while rectal cancer – at 63 years in both genders. Familial forms of CRC develop early in life, with a mean age at diagnosis at roughly 45 years.

· Gender: males tend to be more likely to develop CRC, +87% risk vs women before age 49 and +44% over 50 years old.

· Ethnicity: black men and women have the highest incidence and mortality rates among races, followed by white race, Asians, and American Natives.

· Medical comorbidities: Inflammatory Bowel Disease in medical history triples the chance of developing CRC; with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DMt2) the CRC risk is shown to be approximately five times greater than in people with no DMt2.

· Family history of first-degree relatives with CRC is associated with almost two times higher risk compared to no CRC in family background.

· Untreated FAP (APC gene mutation) set 100% lifetime risk of CRC and Lynch syndrome (DNA MMR genes mutation) – 60% risk.

Modifiable risk factors for CRC

· Physical inactivity: an appropriate physical workout reduces the risk of CRC by 24%.

· Obesity: increasing body mass index (BMI) of every 8 kg/m<sup>2</sup> adds 10% CRC risk.

· Regular alcohol consumption: the risk of CRC rises by 21% with 2-4 drinks/day (moderate) and 52% with ≥4 drinks/day (heavy).

· Cigarette smoking: the risk increases by 6% for 5 pack-years up to 26% for 30 pack-years.

· Eating ≥500 g/week of processed and red meat (beef, pork, lamb) raises CRC risk by 20-30% due to the carcinogenic effects of heme iron molecules.

· People with normal high-fiber dietary patterns, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and cereals, have a 14% decreased risk of CRC development. Conversely, a fiber deficit in consumed food is a moderate risk factor of CRC.

Clinical manifestation & symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting colorectal cancer?

Colon cancer doesn’t always cause symptoms, especially at first. That’s why screening for those over 45 years old is essential.

The initial symptoms may include:

- a change in bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or feeling that the bowel does not empty all the way;

- blood in bowel movement (stool);

- frequent abdominal/pelvic pain, aches, or cramps;

- weight loss without known reason.

Diagnostic route & screening

When, where, and how should colorectal cancer be detected?

Regular CRC screening begins for men and women aged 45 years in the U.S. and 50 in Europe. However, persons with familial history of CRC, genetic syndrome (FAP or Lynch syndrome), and inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) may proceed to the screening earlier than 45 years old.

The screening gives a person without colorectal tumor symptoms information on possible precancerous polyp so that it can be removed before turning into cancer. It includes:

- guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) or the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every 2 years – to identify if there is a silent bleeding from a damaged intestinal polyp;

- flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy every 10 years – to visualize any possible benign adenoma or polyp in the gut.

The screening program is active to age 70-75 years.

If an adult doesn’t follow the screening but presents any symptoms of possible CRC, the tests mentioned above are provided by clinics as diagnostic methods. The diagnosed CRC is classified by the stage of progression and metastasis evidence: from stage 0 (intramucosal carcinoma) through stages I-IIB (the tumor grows into the intestinal wall), then stage IIC-III (the tumor growth into nearby organs by itself or/and spread to 1-7 nearby lymph nodes) and, finally, stage IV (tumor enters liver, lungs, or bones through metastasis).

About 80% of primary CRC diagnoses are patients with stage 0-III tumors, and the remaining 20% are stage IV cancer.

Treatment approaches

What are the options for managing colorectal cancer?

For those CRC lesions which reside locally without lymph nodes and distant organs involvement (stages 0-II), surgical resection of the tumor within a part of the intestine is the primary treatment option. The adjuvant fluorouracil-based (5-FU) chemotherapy for patients with CRC stage II and increased risk of recurrence [the involvement of visceral peritoneum or very abnormal histology] is an option.

Patients with CRC stage III are recommended to receive surgical treatment combined with adjuvant chemotherapy based on one of the following regimes:

- fluorouracil/levamisole (5-FU/LV) OR capecitabine (weaker immunosuppressive adverse effect);

- FOLFOX-4: oxaliplatin/5-FU/LV;

- CAPOX: capecitabine/oxaliplatin.

Stage IV metastatic CRC (mCRC), due to the vast dissemination of secondary lesions, is operable only in 20% of patients whose tumors and metastases can be radically resected. For the rest of mCRC patients, the surgical approach is often combined with palliative chemotherapy to reduce the number and the volume of metastasis.

It is recommended to start with the first-line chemotherapy, such as 5-FU, capecitabine, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, FOLFOXIRI (irinotecan/oxaliplatin/LV/5-FU).

The response rate for the first-line drugs is around 50-54%, leaving roughly half of the patients as a second-line targeted therapy against different cellular factors that support tumor growth:

- bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) combined with FOLFIRI or FOLFOX regime;

- cetuximab (anti-EGFR) alone or combined with FOLFOX/bevacizumab – especially beneficial for KRAS mutation-negative mCRC patients;

- panitumumab (anti-EGFR) combined with FOLFOX-4 – especially beneficial for KRAS mutation-negative mCRC patients;

- aflibercept (anti-VEGF) combined with FOLFIRI;

- ramucirumab (anti-VEGFr2) combined with FOLFIRI;

- trifluridine-tipiracil combined with bevacizumab;

- regorafenib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor);

- encorafenib with cetuximab for BRAF V600E mutations-positive mCRC patients.

The second-line therapy is successful in 20-45% of first-line drug-resistant mCRC patients.

About 4% of mCRC patients have hereditary forms of the disease with specific mutations such as dMMR and MSI-H. For these patient subgroups, immunotherapies were invented. The following drugs are increasing the progression-free survival rate for patients twice better than standard chemotherapy: pembrolizumab (KRAS-negative tumors) and nivolumab/ipilimumab (KRAS-positive tumors).

Prognosis

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

The 5-year relative survival rate for CRC patients is 65%, including 9 out 10 alive patients with stages 0-IIB and 7 out of 10 alive patients with stages IIC-III. The mCRC stage IV is a highly aggressive tumor, which gives a patient, on average, a 3-year 20% and 5-year 10% survival rate if left untreated.

The current diagnostic approach can detect only 40% of CRC cases in the early stages, and the condition might recur following surgery and adjuvant treatment. That’s why regular screening, detecting, and removing polyps at the early stage is crucial; thereby, CRC can be prevented.

Diagnostic & Treatment Management of Colorectal Cancer Disease

Algorithm of diagnosis

What evaluations do CRC patients undergo to identify the best treatment strategy?

It is crucial to understand – both for a patient and a physician – the stage and clinical presentation of the disease so patient treatment and support are of total value. Additionally, in women, the diagnostic algorithm helps to rule out the presence of synchronous breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers.

The diagnostic interventions include:

- Clinical examination: includes palpation (touching) of the abdomen and rectal examination. By doing so, the doctor determines whether the tumor has caused the liver to enlarge and whether it has caused excess fluid in the abdomen, called ascites. The rectal examination serves to identify if there are any signs of blood in the area.

- Endoscopy: allows the doctor to inspect the interior of the bowel for abnormal formation or growths in the inner lining of the intestine using a fine-lighted tube with camera and biopsy tools. If any abnormal lesion is found, the doctor can take a piece of it for histopathological (microscopic) examination. Endoscopy can be performed in different areas, by inserting a short rectoscope, longer sigmoidoscope, or a flexible colonoscope to investigate a target part of the large intestine precisely and carefully. Tumors found within 15 cm of the anus are classified as rectal cancer, whereas any further away from the anus location are called colon tumors. When a rectal tumor is found during a rectoscopy, a complete colonoscopy is also required to check if the pathology resides locally or distributed through the gut.

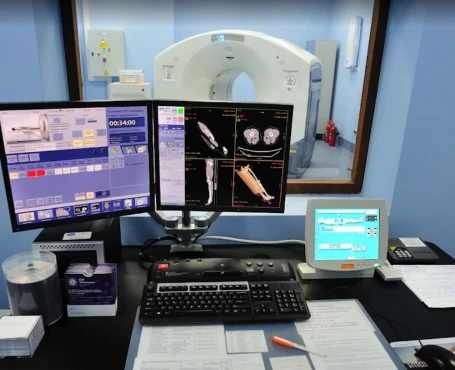

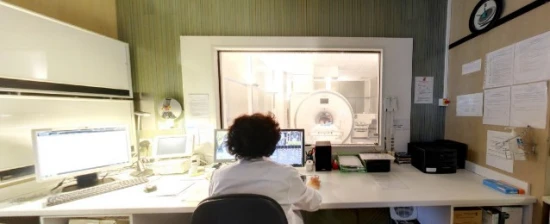

- Radiological investigation: if the endoscopy is challenging to perform, for example, in obstructive tumors, a virtual colonoscopy may be an option. This examination involves a computer tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, after which a computer produces 3-D images from the interior wall of the large intestine.

An outdated but occasionally used radiological option is a double contrast barium enema with barium sulfate (a chalky liquid commonly used in radiological examinations), and air are introduced into the colon via the anus, typically when the right-sided part of the colon is under investigation.

For the endoscopy and virtual colonoscopy, adequate bowel preparation is needed.

Additional radiological techniques may be used to determine the level of the tumor spread and the presence of metastases. They include a CT scan of the chest, ultrasound of the liver, and endoscopic ultrasound. While nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the rectum is a routine diagnostic procedure in rectal cancer, it stays optional in colon cancer. Positron emission tomography (PET) is another way to visualize metastasis in high resolution, but PET scans are not performed routinely due to their cost.

- Laboratory tests: routine blood sample measurements give information on complete blood count and liver/kidney function. Tumor markers monitoring helps to identify a level of a specific protein called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which is sometimes elevated in this pathology. If CRC patients have high CEA levels at initial diagnosis, observing this marker level during and after treatment is wise.

- Histopathological examination: means laboratory investigation of the tumor tissue under a microscope on the biopsy or polyp obtained via endoscopy. As a result, the doctor will have information on specific mutations (such as RAS, BRAF, MLH1, CIN, MSI, etc.) within tumor cells sensitive to target therapy (molecular profiling). Also, the doctor performs histology-assessed tumor staging from 0 to IV, which helps to understand the disease's prognosis and possible regional or metastatic risk.

Treatment routes

What is an appropriate treatment for different CRC stages?

Surgery is the most effective one-step maneuver to treat CRC forms that have not spread to distant sites. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may also be options for people who aren’t healthy enough for surgery or for when complete resection is not possible due to tumor location.

Treating stage 0 CRC

The stage 0 colon tumors have not grown beyond the inner lining of the colon. That is why surgery to take out the cancer via excision of the polyp (polypectomy) through the intestinal lumen (colonoscopy approach) is often the only treatment needed. This procedure is called endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS).

Treating stage I CRC

A more advanced surgical approach can be utilized when the cancer has grown deeper through the intestinal wall but has not spread outside the colon wall itself or into nearby lymph nodes. In the case of polyp-formed CRC stage I, the polypectomy (polyp removal) during colonoscopy via EMR or local excision with a small amount of surrounding healthy tissue on the colon wall via TAMIS is performed. If no cancer cells are at the edges (margins) of the removed piece, no other treatment may be needed.

However, there are following situations when surgical removing a small part of the colon (partial colectomy ≥ 5 cm on either side of the tumor) is a standard treatment in advanced CRC stage I:

- if the tumor presents as high-grade (highly abnormal cells on histology),

- if there are cancer cells at the edges of the polyp, or if the polyp couldn’t be removed completely,

- if the polyp had to be removed in many pieces.

If only part of the colon is removed, it’s called a hemicolectomy, partial colectomy, or segmental resection. The surgeon takes out the part of the colon with the cancer and a small segment of the normal colon on either side. Usually, about one-fourth to one-third of the colon is removed, depending on the size and location of the cancer. A colectomy can be done in 2 ways:

- open colectomy when the surgery is done through a single long incision (cut) in the abdomen (belly);

- laparoscopic-assisted colectomy, also known as minimally invasive surgery - through 3-4 smaller incisions (0,5-2 cm length) in the belly with the use of special manipulation tools and a small camera. Due to minor body damage, patient recovery in this option is much faster, while overall survival rates and the chance of cancer returning are the same compared to open colectomy.

After the operation, the colon’s remaining sections are reattached in three ways: end-to-end, side-to-side (prevents lumen narrowing), or end-to-side (connects smaller lumen with the larger one). In the advanced CRC stage, end-to-end and side-to-side connections (anastomoses) are options of choice. At least 12 nearby lymph nodes are also removed so they can be checked for cancer.

Treating stage II CRC

The CRC at stage II penetrates the intestinal wall and may invade nearby tissue. Patients in this group receive surgery as a standard cure method - a partial colectomy along with nearby lymph nodes removal. Another name for this operation is En bloc colonic and mesentery resection since cancer lesions in the intestinal wall and infiltrated fat tissue are resected without breaking the tumor capsule.

Suppose the involved area is too large to perform an anastomosis on the resting bowel ends immediately after the resection. In that case, the surgeon will move one end of the intestine through an opening in the abdominal wall and connect it to a bag or pouch. This is called colostomy and it’s done so that stools that would normally move through the intestine to the rectum instead pass through the opening in the abdomen into the pouch. The colostomy bag must be manually emptied. The colostomy is often only used as a short-term solution and consequently is replaced by ileocolonic anastomosis, which re-connects the small intestine and colon.

If a CRC stage II tumor looks very abnormal when viewed closely in the lab, or it has grown into nearby blood or lymph nodes, or there is a blocked (obstructed) lumen / perforated (hole) colon wall, the neoadjuvant chemotherapy for 3-6 months is recommended, including capecitabine or fluoropyrimidine (5-FU) treatment.

The medication treatment starts as adjuvant therapy within eight weeks after the surgery at stages II-IV, when the tumor can involve the whole depth of the bowel, raising intestine wall perforation awareness.

Treating stage III CRC

Stage III colon cancer is widespread to nearby lymph nodes, which is why surgeons often perform partial colectomy, followed by 3-6 months adjuvant treatment (5-FU, oxaliplatin, capecitabine) to prevent further spreading of the disease without mutations dMMR or MSI-H. If these mutations appear, neoadjuvant immunotherapy (pembrolizumab, etc.) is recommended.

Radiation therapy may accompany the surgery when some advanced stage III tumors are found to be attached to a nearby organ:

- before the surgery, radiation therapy helps to shrink a tumor and make it easier to remove;

- after the surgery - double-check for cancer cell killing in a region;

- during the surgery - intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) - to clean the area from possible tumor cells left.

Treating stage IV CRC

The challenge with terminal stage IV CRC is that it is a metastatic tumor (mCRC) that involves the liver, lungs, and bones. That’s why the surgery bears only a palliative goal, meaning the partial colectomy or the total colectomy (removing all the colon) would not have a decisive effect on the patient’s recovery.

The number of operable cases in CRC decreases with stage growth. Starting from stage I CRC– about 90% of patients are surgery-eligible - to metastatic CRC (mCRC) stage IV, where due to comorbidities, there is about a 20% chance to be eligible for radical surgery.

At CRC stage IV, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy are the first-line treatments.

Radiation therapy includes three types:

- External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) - helps to focus the radiation beam on the cancer from a machine outside the body. There are techniques, such as three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT), intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), have been shown to treat lungs and liver CRC metastases;

- Internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy) - treats rectal cancer since the radiation source is put inside the rectum next to or into the tumor;

- Radioembolization - means injecting tiny beads (called microspheres) coated with radioactive yttrium-90 (Y-90) into the hepatic artery. The beads lodge in the blood vessels near the metastasis in the liver, where they give off small amounts of radiation to the tumor site for several days.

Chemotherapy treatment of peritoneum (inner wall of the abdomen) metastatic lesions in mCRC includes:

- Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) uses high-concentration drug mitomycin-C combined with hyperthermia 39-43°C and high-pressure flow;

- Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosolized Chemotherapy (PIPAC) uses high pressure to push chemo drug (oxaliplatin) into metastatic cells.

Mutation-specific approach for CRC (immunotherapy)

Are there any personalized medicine options?

A few options for standard treatment-resistant mutation-based personalized approach as a first-line therapy were developed in the last decade. The immunotherapy drugs (bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, etc.) target specific molecular proteins from a group called Growth Factors, which provide cancer rapid growth and spread when genetic mutations trigger its overproduction. The medications block the ability of cells to produce the growth factors, thus shrinking the tumor.

Follow-up & surveillance strategy

How do you make sure the cancer will not return?

Monitoring of CRC blood markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may help to catch a cancer recurrence after initial treatment at an early stage.

Localized Colon Cancer stage 0-III surveillance program:

- when surgery is not possible due to significant comorbidities, surveillance colonoscopy within six months after polyp removal with close oncological follow-up, including a CT scan to detect lymph node recurrences, is recommended;

- if the surgery went successfully, repeat colonoscopy in 1-2 years and 3-5 years thereafter;

- CEA determination and physical examination every 3-6 months for three years and every 6-12 months at years 4 and 5 after surgery;

- CT scans of the chest and abdomen every 6-12 months for the first three years for high-risk recurrence stage II-III CRC patients.

Metastatic Colon Cancer stage III-IV surveillance program:

- for patients receiving active treatment, a CT scan or MRI plus CEA measurement every 8-12 weeks is recommended;

- after radically resected metastatic disease – CT or MRI plus CEA levels every three months during the first two years and every six months thereafter.