Disease Types

What are the bone metastases?

Bone metastases occur when cancer cells spread from their original site to the bones. This is a common complication of advanced cancers, particularly breast, prostate, and lung cancers.

Approximately 95% of patients with multiple myeloma, 70-85% with advanced breast or prostate cancer, and 40% of those with advanced lung or kidney cancer will develop bone metastases [Nature, 2020].

The spine, pelvis, ribs, and long bones of the arms and legs are the most frequent sites affected by this metastatic spread. Bone metastases can lead to significant health issues, including severe pain, fractures, and high calcium levels in the blood, which can be life-threatening if not managed properly.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of bone metastases?

The main problem with bone metastases is that cancer cells, once they spread to the bones, disrupt the normal bone remodeling process. Healthy bones are continuously in a balanced cycle of breakdown and formation. However, metastatic cancer cells can produce chemicals that overstimulate osteoclasts or osteoblasts, weakening bones or abnormal bone growth. Some cancers, such as breast and prostate, have a greater tendency to spread to the bones, partly due to the favorable conditions in the bone microenvironment for tumor growth.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting bone metastases?

Bone metastases can occur in any bone but most often affect the spine, pelvis, ribs, and long bones. Patients with bone metastases frequently experience pain in the affected bone. The metastases can also lead to heavy complications like bone fractures or spinal cord compression, which requires urgent medical attention. Excess calcium in the blood from bone breakdown can cause nausea, confusion, and kidney problems [Cancer.org, 2024].

More severe complications of bone metastasis may involve:

- Dehydration, confusion, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation.

- Increased infection risk, breathlessness, paleness, bruising, and bleeding (due to low healthy blood cell levels in the bone marrow).

- Pain, weakness, numbness, paralysis, loss of sensation in the legs, and incontinence.

Diagnostic Route

When, where, and how should bone metastasis be detected?

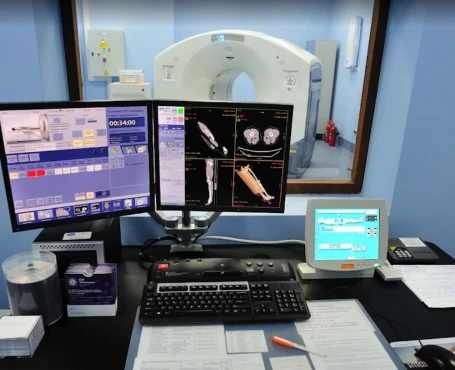

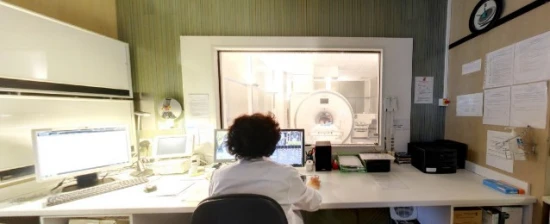

Diagnosing bone metastases typically involves a combination of imaging studies and laboratory tests [NIH, 2023]:

- Imaging techniques, such as X-rays, bone scans, MRI, CT scans, and PET scans, are used to detect the presence and extent of bone metastases.

- Bone biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and determine the type of cancer.

- Laboratory tests like blood tests can assess calcium levels and other markers indicating bone turnover or cancer progression.

Treatment Approaches

What are the options for managing bone metastasis?

Diagnosing bone metastases typically involves a combination of imaging studies and laboratory tests:

- Imaging Techniques: X-rays, bone scans, MRI, CT scans, and PET scans are used to detect the presence and extent of bone metastases.

- Bone Biopsy: In some cases, a biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis and determine the type of cancer.

- Laboratory Tests: Blood tests can assess calcium levels and other markers indicating bone turnover or cancer progression.

Treatments for bone metastases vary depending on the underlying cancer and the size and location of the metastases. Treatment is usually palliative, meaning the goals are to slow the progression of cancer, reduce symptoms, and improve quality of life. It's important to understand that treatment of bone metastases is rarely curative. The oncologist may recommend one or more of the following approaches:

Radiotherapy uses ionizing radiation to damage the DNA of cancerous cells, causing them to die. It uses external beams aimed at the area of bone metastasis and can be very effective in relieving pain. This primary treatment for localized bone pain can reduce about 70-80% of patients. Radiotherapy is also used to relieve pressure on the spinal cord in cases of spinal cord compression. It is often used after surgical treatments, such as for spinal cord compression and to fix or prevent fractures of the arms or legs [ASTRO, 2024].

Surgical treatment for bone metastases may be considered if there is spinal cord compression, severe pain, and/or a bone fracture caused by bone metastasis. Radiotherapy may also be received after surgery to help strengthen the bone. Whether surgery is recommended depends on which bone is affected, where the cancer is located, what other cancer treatments are being received, and the patient's overall health.

Bone-targeted agents treat bone metastases arising from all types of cancer. These drugs work by reducing bone resorption, thereby helping to strengthen bones. They can reduce bone pain, fracture risk, and calcium levels. It's important to understand that bone-targeted agents are not anticancer therapies, but they can maintain or improve quality of life by reducing pain and complications associated with bone metastases.

Two types of bone-targeted medications are used:

- Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks a protein called RANKL, reducing bone resorption.

- Bisphosphonates target areas of high bone turnover, causing osteoclast cells to die and reducing bone resorption. Examples include zoledronate, pamidronate, clodronate, and ibandronate.

Prognosis & Follow-up

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with bone metastases?

The prognosis for patients with bone metastases can vary greatly, depending on the type of primary cancer, the degree of bone involvement, and the patient's overall health. Generally, the presence of bone metastases suggests advanced disease and a less favorable prognosis. However, with contemporary treatment options, many patients can achieve meaningful pain relief and enhanced quality of life. Five-year survival rates for those with bone metastases tend to be lower, ranging from 10-40%, depending on the specific cancer type [Yang et al., 2023].

What treatments are available to prevent bone metastases?

Bisphosphonate treatment may be recommended in some circumstances to help prevent the development of bone metastases. This can be particularly important for patients considered at high risk of their cancer returning after treatment. However, the best evidence for the benefits of this type of preventative treatment has been observed in post-menopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Currently, treatment for the prevention of bone metastases is not recommended in any other type of cancer apart from breast cancer.

Individuals diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer who are post-menopausal (or pre-menopausal and receiving a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog) and are considered at high risk of their cancer returning may be prescribed a bisphosphonate (usually zoledronate, clodronate or ibandronate). Bisphosphonate treatment typically starts at the same time as other systemic therapies (such as chemotherapy) and continues for 2-5 years. Bisphosphonates can also lower the risk of treatment-induced bone loss [Tsukamoto et al., 2021].

What is cancer treatment-related bone loss?

The rate of bone loss naturally increases with age in both men and women. However, some cancer treatments can accelerate this bone loss, leading to osteoporosis. These treatments include:

-

Hormone therapy for breast cancer that reduces estrogen levels: long-term use of these drugs can cause bone loss and increase the risk of fractures. Not all hormone therapies for breast cancer cause this issue.

-

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer: drugs that lower testosterone levels can lead to bone loss.

-

Chemotherapy: certain types can affect the ovaries or testicles, reducing estrogen in women and testosterone in men, resulting in bone loss.

-

High-dose or long-term steroid treatment can cause bone loss.

-

Removal of both testicles in men or the ovaries before menopause in women reduces hormone levels and leads to bone loss.

-

Radiotherapy of the ovaries before menopause lowers estrogen levels and can cause bone loss. Radiotherapy of the pelvic area can also make bones unable to cope with regular activity, increasing fracture risk.

-

Not all cancer treatments increase the rate of bone loss. The oncologist can explain if a specific treatment puts the patient at risk of osteoporosis.

What therapies are available to prevent cancer treatment-related bone loss?

Individuals receiving cancer treatments known to accelerate bone loss can take several steps to reduce the risk of osteoporosis:

- Stop smoking;

- Reduce alcohol intake;

- Eat a calcium-rich diet;

- Engage in weight-bearing exercises;

- Take a vitamin D supplement daily.

For women on aromatase inhibitors or undergoing ovarian function suppression for breast cancer and men on androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer, bone-targeted agents may be recommended if there is a risk of osteoporosis. These drugs reduce bone resorption, thereby strengthening bones and lowering fracture risk.

Two types of bone-targeted agents used in this context are Denosumab and Bisphosphonates drug class [Yang et al., 2023].