Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common are the spinal tumors?

A spinal tumor is an abnormal growth of cells within or close to the spinal cord and vertebrae. In 30% of cases of this disease, the lesion in the spine grows and multiplies abnormally from cells of the central nervous system (CNS) within dura - the membrane surrounding the spinal cord - and extradural tissues (bones, cartilage and ligaments), - which is called a primary tumor. If abnormal cells have spread to the spine from a tumor in another body part, this is called a secondary tumor or a metastasis. Metastasis of the spine is more prevalent – around 70% of spinal tumors [CancerResearchUK, 2023].

In the United States, 1 out of 100,000 people develop spinal cord tumors annually, while secondary (metastatic) spinal tumors have an incidence rate of approximately 10 per 100,000 individuals each year [Amadasu et al., 2022].

Primary tumors are graded according to the speed at which they are growing. Slower-growing tumors are given lower grades (grades 1 and 2), and faster-growing tumors are given higher grades (grades 3 and 4). Depending on the grade, the spinal lesion is referred to as a tumor as “non-malignant” or “malignant.”

Non-malignant spinal tumors are typically slow-growing and non-spreading, posing a low risk of developing secondary tumors in other body areas. Nonetheless, they have the potential to reach a significant size, leading to tissue compression within the spine.

Historically, grade 1 and grade 2 spinal tumors were often referred to as ‘benign,’ but the use of this term is becoming less common. This change reflects the understanding that all spinal tumors have the potential to cause significant harm, even if they are slow-growing and less aggressive upon discovery.

High-grade (grade 3) spinal tumors are known as “malignant” spinal tumors and are cancerous. They can spread and destroy nearby tissue, with their invasiveness dependent on their level of malignancy. While they can lead to tumor growth in other parts of the body, this is rare for spinal cord tumors.

While primary spinal tumors may be non-malignant or malignant based on their grade, secondary (metastatic) spinal tumors that originate from a malignant tumor elsewhere in the body are always considered malignant and are not graded.

There are two types of intradural primary spinal tumors based on the location within the spinal cord (intramedullary) or external to the spinal cord (extramedullary) [Amadasu et al., 2022].

Intramedullary spinal tumors consist of neural cells that make the spinal cord part of the central nervous system, such as astrocytomas (making up 40% of intramedullary spine cord lesions), ependymomas (55%), hemangioblastomas (< 3%) and gangliogliomas (1-2%).

Extramedullary tumors are growths outside the cord within the protective covering known as the dura mater. The most common subtypes here include meningiomas (25-30%), schwannomas (30%), neurofibroma (5-10%), and chordomas (<5%).

The extradural spinal tumors include osteosarcomas, Ewing sarcomas, multiple myeloma (all three mostly affect the lumbosacral area), chondrosarcoma (common in the thoracic area) and chordomas (mostly in the sacrum).

When it comes to metastatic tumors, they commonly originate from:

1. Breast Cancer – 20-25% of metastatic spinal tumors.

2. Lung Cancer –15-20%.

3. Prostate Cancer – 10-15%.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of spinal tumors?

There are two evidence-based risk factors for primary spinal tumors: genetic abnormalities and a family history of spinal cancer.

Genetic mutations in:

- NF1 and NF2 genes are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, increasing the risk of spinal tumors (schwannomas and meningiomas) by 50%.

- VHL Gene leads to von Hippel-Lindau disease, which can cause hemangioblastomas [CancerResearchUK, 2023].

Having a family history of cancer can increase an individual’s risk by 20-30%.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting a spinal tumor?

Spinal tumors can show a range of symptoms, which can vary based on where they’re located and what size they are. These signs may include:

- Discomfort in or near the spine.

- Night pain: continuous back or neck discomfort that may extend to other body areas. Neck or lower back pain is often caused by degeneration in the joints and discs or a slipped disc (disc protrusion). If rest does not provide relief, it could indicate a tumor. Discomfort that spreads from the back throughout the body may suggest nerve involvement.

- Neurological issues: weakness, numbness, or a tingling sensation in the arms or legs. However, the unusual sensations and pain radiating down a limb from the spine are frequently associated with a slipped disc in the neck or lower back. Disc protrusions are much more prevalent than tumors.

- Problems affecting both legs: worsening leg numbness, tingling, or weakness could signal a spinal cord or nerve issue. This symptom might be caused by a tumor putting pressure on the spine. It’s essential to report these symptoms to a physician, especially if the patient has a history of cancer.

- Bladder and bowel control issues: such as with either leakage of urine or difficulty in emptying the bladder/bowel.

- Spinal Abnormalities: curves or deformities in the spine.

Algorithm of Diagnosis

What evaluations do spinal tumor patients undergo to identify the best treatment strategy?

Patients diagnosed with spinal tumors typically experience a variety of symptoms, such as back pain, neurological issues, and occasionally systemic manifestations like weight loss or fever. The diagnostic journey commences with a comprehensive clinical assessment involving an in-depth review of medical history and thorough physical examination with a profound look for neurologic deficits and the presence of cancer-related issues in family background.

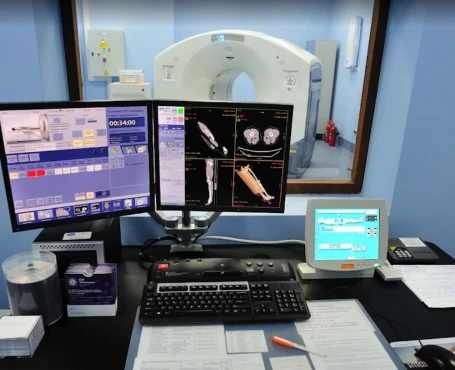

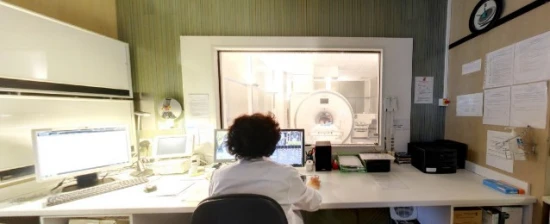

Spine lesion visualization through imaging techniques is the next step due to its non-invasive and full-depth availability to mark damaged tissue and clarify the tumor aggressiveness stage.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the best way – the so-called “gold standard” - to evaluate spinal tumors. It gives detailed images of the spinal cord, nerve roots, and surrounding structures for precise localization and characterization of the tumor. MRI can distinguish different types of spinal tumors based on their appearance on imaging sequences [Cancer.org].

- Computed Tomography (CT) scans are valuable in assessing bone impact and offering precise pictures of the bony framework of the spine. They are frequently employed alongside MRI for a thorough evaluation [HopkinsMedicine.org].

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans are crucial in evaluating metabolic activity and detecting metastatic disease. Combined with CT, PET provides both functional and anatomical information to enhance diagnostic accuracy [CancerResearchUK].

When the tumor’s nature remains unclear after imaging, a biopsy may be necessary to obtain a tissue sample for histopathological examination. This can be accomplished through minimally invasive methods, such as percutaneous needle biopsy or open surgical biopsy.

Laboratory tests, including blood tests and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, may be conducted to assess for tumor markers and other indicators of systemic involvement. The spinal tumor lab test panel involves a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and assessment of specific tumor markers, such as CEA, CA-125, PSA, and NF1/2 gene mutations [Amadasu et al., 2022].

Treatment routes

What is an appropriate treatment for different spinal tumor stages?

Surgical management plays a crucial role in treating spinal tumors, mainly when the aim is to alleviate pressure on the spinal cord, stabilize the spine, or altogether remove the lesion. The selection of surgical methods from the list described below depends on factors such as the location and size of the tumor, its type, and the patient’s overall well-being.

- Decompression Surgery: Intended to alleviate pressure on the spinal cord and nerves. This may include taking out a portion of the vertebra (laminectomy) or other elements that are compressing the spinal cord.

- Stabilization Surgery: Frequently carried out with decompression surgery to offer structural reinforcement to the spine. This may involve utilizing rods, screws, and bone grafts.

- Complete Resection: When possible, complete surgical elimination of the tumor is undertaken. This is frequently the objective for benign tumors or instances where the lump is clearly defined and reachable.

Radiation therapy manages tumor growth, alleviates discomfort, and enhances neurological function. It can be employed as a primary treatment, adjunct therapy post-surgery, or for relief in metastatic disease.

- External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) is the most prevalent form of radiation therapy where high-energy beams are targeted at the tumor outside the body. Typically, it is administered over several weeks.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery (STSR) is an exact type of radiation therapy that administers a concentrated dose of radiation to the tumor either in one session or across multiple sessions with techniques such as CyberKnife and Gamma Knife exemplify SRS applications [Amadasu et al., 2022].

Chemotherapy is less commonly used for primary spinal tumors but is an important treatment modality for recurrent types of intramedullary spinal tumors and metastatic disease. Standard Chemotherapy Regimens may include drugs like temozolomide for gliomas or other chemotherapeutic agents (methotrexate, carboplatin) tailored to the specific type of tumor [Anticancer Research, 2022].

Targeted therapies are medications created to precisely aim at molecular pathways related to the growth and sustainability of tumors.

- Bevacizumab is an angiogenesis inhibitor that blocks the growth of blood vessels in the tumor. Bevacizumab demonstrated its effect in high-grade meningioma multiple schwannomas with >20% tumor volume in up to 60% of cases [Strowd, 2020].

- Erlotinib is an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor utilized for tumors with EGFR mutations, such as EGFR-positive chordoma (first-line treatment) [Frontiers in Oncology, 2019].

Immunotherapy utilizes the body’s immune system to combat cancer, making it an emerging area in the treatment of spinal tumors. One example is Pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor that helps the immune system identify and attack cancer cells. Another option is Nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor used in gliomas, including those affecting the spine.

Follow-up & prognosis

How do you make sure the spinal tumor will not return?

The outlook for patients with spinal tumors can differ significantly based on the kind, location, and stage of the cancer.

- Primary Spinal Tumors: The 5-year survival rate for primary spinal tumors varies by type. For instance, benign tumors like meningiomas have a high 5-year survival rate of approximately 85-90%, while malignant tumors such as chordomas have a lower rate of about 50-60%.

- Metastatic Spinal Tumors: The prognosis for metastatic tumors largely relies on the primary cancer type and overall disease burden. Generally, the 5-year survival rate for metastatic spinal tumors is lower at around 20-30%. Malignant intramedullary spinal tumors have a challenging prognosis, with a high likelihood of local recurrence at 50% and metastasis to the bone and lung at 33% [Amadasu et al., 2022].

Prognosis

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

The prognosis for tumors varies based on the type and stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. Primary spinal tumors generally have a higher survival rate than secondary tumors. The 5-year survival rate for these tumors can range between 70-90% and is influenced by the specific type and location of the tumor.

Metastatic spinal tumors typically have a lower prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 20-40%, depending on the origin of the primary cancer and its response to treatment.

Regular follow-up is essential to monitor for recurrence and address long-term side effects following treatment.

- Every 3 Months: In the two years post-treatment, routine physical exams and necessary imaging are conducted to detect any signs of recurrence.

- Every 6 Months: From the third to fifth years post-treatment, emphasis is placed on monitoring for recurrence and managing lingering side effects effectively.

- After five years, patients usually switch to check-ups. These appointments involve examinations, imaging tests, and evaluations for delayed side effects or additional cancers. Screening for forms of cancer is also part of the long-term follow-up, as there is a risk of developing cancers from radiation and chemotherapy.