Overview and treatment options of gliomas

Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

A primary brain tumor is a mass of abnormal cells that start in the brain. These pathological formations can arise from brain cells, the meninges (membranes) around the brain, nerves, or glands.

Primary brain tumors can be benign or malignant. Being a benign tumor means accumulating a group of visibly (under a microscope) normal cells. Benign brain tumors grow slowly and stay in their capsule. On the other side, malignant brain tumors (called cancer) grow rapidly and typically invade (infiltrative pattern) surrounding the healthy brain (do not have a capsule around). Brain cancer is life-threatening due to the changes it causes to the vital structures of the brain [hopkinsmedicine.org].

According to the National Brain Tumor Society, one million Americans are living with a brain tumor. Around 94,000 U.S. citizens receive a primary brain tumor diagnosis every year, and 5.7% of them are children ages 0-19 years [braintumor.org].

The incidence of primary malignant brain tumors (brain cancer) is approximately 7 per 100,000 individuals [Schaff et Mellinghoff, 2023], which is around 28% of all brain tumors.

Gliomas can occur at any age and are the most prevalent type of adult primary malignant brain tumor, accounting for 78% of brain cancer [aans.org], as well as in children – 51.2%, according to the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States [cbtrus.org].

Gliomas may arise anywhere in the central nervous system (CNS) segments: the brain and the spinal cord. They infiltrate surrounding brain tissue and usually do not spread outside the CNS.

Gliomas' aggressiveness – the tumor growth rate and invasion of surrounding brain regions – follows a scale from I to IV by the WHO Classification of Tumors of the CNS [braintumor.org]. Grade I tumors, which occur mainly in childhood, are associated with the best prognosis. Grade II (low-grade gliomas) represent slowly growing and infiltrative tumors with intermediate prognosis. On the other hand, grade III (anaplastic) and grade IV (glioblastoma) tumors are both considered to be high-grade gliomas, as they are aggressive and generally have the least favorable prognosis [esmo.org].

Gliomas are a big group of brain cancer, divided into subgroups according to the type of glia – "supportive" nervous cells - which they derive from, such as [aans.org]:

- From astrocytes (provide control of nutrients to the CNS): astrocytoma (50% of gliomas) has a better prognosis in children (low-grade tumor) and worse (high-grade) in adults.

- From oligodendrocytes (produce nerves insulating shell for fast signal transmission): oligodendrogliomas – the prevalence is low-grade.

- From ependymal cells (recover brain structures after trauma): ependymoma – often low-grade.

- From the mix of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes - Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), high-grade (IV) with poor prognosis, more common in adults in their 50-70 years.

- From glial stem cells – Medulloblastoma – high-grade anaplastic (III) tumor, which commonly arises in children but is usually responsive to radiation and chemotherapy.

Causes & Risk Factors

What is the primary issue of glioma?

It is unclear why glioma occurs; very few risk factors have been identified. It is essential to know that a risk factor increases the risk of cancer occurring but is neither necessary nor sufficient on its own to cause cancer. A risk factor is not a cause in itself. Therefore, some people with one or more risk factors will never develop glioma; others without any of these may develop glioma.

The risk factors of gliomas are:

- Ionizing radiation such as nuclear weapons exposure or previous head radiation treatment, as patients who undergo cancer therapy during their childhood are at risk years or even decades later;

- Family history of one or more gliomas in the same family is associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk.

- Genetic syndromes such as Cowden syndrome, Turcot syndrome, Lynch syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type I when one or multiple genes may carry a carcinogenic mutation.

Clinical Manifestation & Symptoms

What signs should one anticipate while suspecting glioma?

All brain tumors share one specific feature. They grow in a closed bone chamber of a skull (cranium) and can directly (mechanically) destroy brain cells by increasing pressure in the head. The high-level intracranial pressure triggers destabilization of the muscular tonus and body movement, causing seizures. It also suppresses brain regions' standard intercommunication, resulting in neuronal functional damage.

Thus, the most common clinical signs of brain tumors include headache with nausea, vomiting, double vision, and drowsiness (50%), followed by seizures (20%-50%) and loss of body function such as movement, vision, hearing, etc. (neurocognitive impairment) in every third patient [Schaff et Mellinghoff, 2023].

When glioma arises from the spinal cord, pain, numbness, and/or weakness in the lower part of the body, and/or loss of control of the bladder or bowel may be present.

Diagnostic Route & Screening

When, where, and how should glioma be detected?

Usually, when the glioma starts causing the symptoms, the doctor at the clinic launches a check-up, which includes a clinical examination of alternated sensation, movement coordination tests, and cognitive status evaluation. Additionally, the doctor may do a general physical examination of the breast, abdomen, and skin to exclude metastatic origin of CNS symptoms.

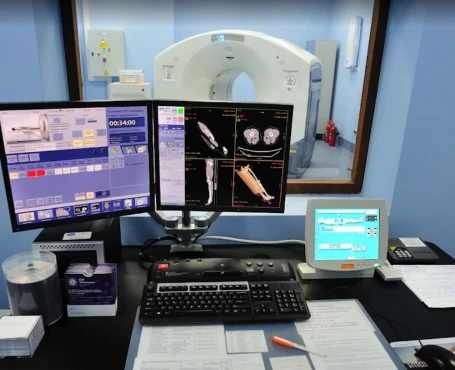

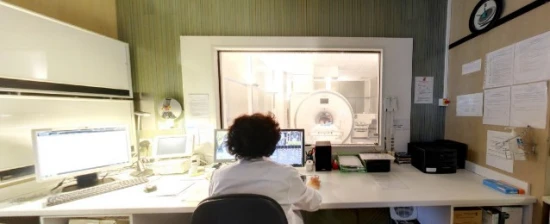

Then, a radiological examination, such as computer tomography (CT scan) or nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, is performed, so it aims to help locate the lesion.

Stereotactic/open biopsy

A biopsy is not a treatment for the tumor, but an analysis of the tissue removed by biopsy will allow the best treatment to be planned. A stereotactic biopsy is a less invasive way to obtain the tissue sample. In contrast, an open biopsy is surgery that uses local or general anesthesia to remove the tissue needed for the diagnosis.

The data the physician gets from the previous steps may be combined with histopathological (laboratory) examination of tumor tissue samples, which in some cases is received on biopsies (small cut of tumor operation) through a little incision. The biopsy serves as the only method that can definitively confirm a diagnosis of glioma. However, the histopathological examination can yield more precise results when carried out at experienced centers where pathologists (the medical specialists who examine your tissue after it has been removed) have particular experience in analyzing brain tumors. Therefore, a careful review of tumor cells by an expert neuropathologist is crucial.

Treatment Approaches

What are the options for managing glioma?

Surgery

Regardless of the glioma subtype, surgery (surgical resection or stereotactic/open biopsy) represents an essential component of treating all newly diagnosed gliomas.

• Surgical resection

Surgical resection of the tumor is the preferred initial treatment for most gliomas. Surgery is aimed to be as complete as possible. The reason for this is that maximal tumor resection has been shown to result in longer survival and allow for more effective postoperative therapies to be given. But if such radical surgery is expected to impair neurological function, it should be aimed just at removing as much tumor as is safely possible, sparing healthy tissues. In addition, surgical removal of the tumor provides a sufficient amount of tissue for both an accurate histopathological diagnosis and molecular characterization of the tumor.

• Stereotactic/open biopsy

Suppose surgery is not safely feasible, mainly due to tumor location (e.g., surgically inaccessible region or a region that carries a high risk for significant impairment of neurological function) or due to a deteriorated clinical condition. In that case, a stereotactic or open biopsy may be considered to obtain tissue for a diagnosis. A biopsy is not a treatment for the tumor, but an analysis of the tissue removed by biopsy will allow the best treatment to be planned. A stereotactic biopsy is a less invasive way to obtain the tissue sample. In contrast, an open biopsy is surgery that uses local or general anesthesia to remove the tissue needed for the diagnosis. In experienced hands, a stereotactic biopsy provides sufficient tissue for a correct histopathological diagnosis in more than 95% of cases. However, open biopsy may be preferred to provide as much tumor tissue as possible for both diagnosis and molecular characterization.

Radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy

Postoperative treatments mainly consist of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. However, their use differs according to the subtype of glioma.

• Low-grade glioma (WHO grade I and grade II)

Low-grade gliomas comprise the histological types of astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma.

- Radiotherapy

Postoperative radiotherapy is the standard treatment for low-grade gliomas. It is usually administered in 28 sessions over six weeks. Nevertheless, not all patients who undergo resection of a low-grade glioma should be treated with radiotherapy. That is because these patients may have a longer/slower natural history of disease even in the absence of postoperative treatment.

However, postoperative radiotherapy should always be considered in the presence of three or more of the following factors, which suggest a higher likelihood of tumor recurrence:

• tumors greater than 5 cm in diameter,

• age > 40 years,

• absence of an oligodendroglial component at histopathological examination,

• tumors extending from one brain hemisphere to the other,

• presence of neurological deficits before surgery.

- Chemotherapy

Temozolomide chemotherapy given orally is the preferred treatment option for patients not deemed eligible for surgical resection and/or radiotherapy because of tumor location and tumor dimension/appearance at MRI, respectively. Also, temozolomide can be used if/when the disease recurs following radiotherapy.

There is some evidence suggesting that tumors with genetic loss on chromosomes 1p/19q might be more sensitive to chemotherapy as compared to low-grade gliomas without this alteration.

- Anaplastic glioma (WHO grade III)

Similarly to low-grade gliomas, anaplastic gliomas comprise the histological types of astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma. However, they differ from low-grade glioma because of some histological and/or radiological characteristics, which suggest a more aggressive behavior of the tumor.

- Radiotherapy

Postoperative radiotherapy is the standard treatment for anaplastic astrocytoma. It is usually administered in 33 sessions over 6.5 weeks. Radiotherapy alone may also be considered for anaplastic oligodendroglioma and oligoastrocytoma without genetic loss on chromosomes 1p/19q.

On the other hand, radiotherapy given either before or after chemotherapy should be considered for anaplastic oligodendroglioma and oligoastrocytoma with genetic loss on chromosomes 1p/19q (mutation).

- Chemotherapy

Postoperative chemotherapy of the orally administered chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide or the three-drug chemotherapy regimen called PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine) should be considered as an alternative to radiotherapy for anaplastic gliomas. Between the two regimens, temozolomide is usually preferred because of its greater tolerability and ease of administration. Genetic loss on chromosomes 1p/19q identifies the anaplastic tumors with an oligodendroglial component, which are more sensitive to chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy.

- Glioblastoma (WHO grade IV)

Postoperative treatment of glioblastoma may differ according to some of your characteristics (i.e., age, performance status) and histopathological/molecular features of your tumor (i.e., MGMT status of the cancer).

- Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy

The concurrent administration of chemotherapy during radiotherapy and then chemotherapy on its own for a while after radiotherapy is the standard postoperative treatment of patients with glioblastoma up to 70 years of age; it is also the preferred treatment approach for fit elderly patients older than 70 years whose tumor has tested positive for the presence of MGMT gene methylation.

- Chemotherapy consists of the orally administered drug called temozolomide, which interferes with the mechanism of DNA replication of cancer cells. Temozolomide is administered daily from the first day of radiotherapy and for the whole duration of it. At the end of radiation, after a short treatment break (approximately four weeks), temozolomide is resumed at a higher dosage for at least six cycles (six months) of therapy. Although adding temozolomide to radiotherapy benefits most patients with glioblastoma, it is essential to know that the most significant advantage is observed in patients whose tumor is detected positive for MGMT gene methylation testing.

- Radiotherapy is administered concurrently with temozolomide for five days a week for a total of 6 weeks, i.e., in 30 separate sessions.

- Radiotherapy

Elderly patients older than 70 years who are not deemed eligible for concurrent chemo-radiotherapy because of deteriorated performance status and/or because their tumor has tested negative for the presence of MGMT gene methylation are adequately treated with radiotherapy alone using a hypo-fractionated schedule. A hypo-fractioned schedule involves administering higher daily doses of radiotherapy over a shorter period. Hypo-fractionated radiotherapy alone is also appropriate for elderly patients in whom no information is available on the MGMT status.

- Chemotherapy alone

Elderly patients older than 70 years who are not deemed eligible for concurrent chemo-radiotherapy may be adequately treated with temozolomide chemotherapy, provided their tumor has tested positive for the presence of MGMT gene methylation.

Medications to relieve symptoms of a glioma

The symptoms and signs mentioned in the section about diagnosis can improve or even disappear if effective therapies are used to treat glioma successfully. However, the following medications are used to control effectively, at least in part, tumor symptoms:

• Anti-epileptic drugs

Anti-epileptic drugs are very effective medications for patients who have seizures. However, these drugs should not be used for the prevention of seizures in patients who have never experienced one. There are several types of anti-epileptic drugs. Nevertheless, only a few anti-epileptic drugs (lamotrigine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, or topiramate) offer the advantage of lack of interference with the commonly prescribed chemotherapeutic agents. Clinical studies have demonstrated that temozolomide can be safely administered with any type of anti-epileptic drug.

• Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids alleviate patients’ symptoms by reducing tumor-associated inflammation (called edema), which usually forms around the tumor and contributes to symptoms by increasing intracranial pressure. Therefore, corticosteroids are indicated if edema is detected at radiological tests or if the responsible physician decides to start corticosteroid treatment based on signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.

Unfortunately, the downside of corticosteroids is that their long-term use can be associated with some side effects (e.g., Cushingoid or moon face, a condition in which fat accumulates to the sides of the face, giving it a rounded appearance, also increase in blood glucose levels which therefore should be monitored at each visit, increased risk of infection, osteoporosis, muscle weakness, impaired wound healing). For this reason, upon improving symptoms, the dose of corticosteroids should be gradually reduced to find the lowest effective dose or eventually discontinued if symptoms resolve and/or edema disappears due to effective tumor treatment.

• Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation using coumadin derivatives (i.e., warfarin) is feasible in glioma patients experiencing thromboembolic events; however, low-molecular-weight heparin is often preferred due to a favorable safety profile.

Source: ESMO Guidelines

Prognosis

How does cutting-edge science improve the lifespan and quality of life for those with the disease?

The five-year relative survival rate for all patients with both benign and malignant primary brain tumors is 76%. For adult patients with malignant brain tumors, the five-year relative survival rate is 35.7%, whereas for pediatric patients – it is nearly 76%. Patients with glioblastoma, the most common form of primary malignant brain tumors, survive the five years following diagnosis in 6,9% of cases, with median survival at eight months [braintumor.org].

Three molecular glioma markers can either provide information on the prognosis of the tumor or help guide treatment decisions:

- Genetic loss on chromosomes 1p/19q (mutation) defines a slower course of oligodendrogliomas or GMB and shows particular sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

- The IDH gene 1 or 2 mutation is associated with better survival regardless of treatment in low-grade and anaplastic gliomas and with better prognosis (vs IDH-mut negative) in glioblastoma.

- MGMT gene methylation (mutation) reflects more sensitivity of glioblastoma to tomozolomide.

Overview and treatment options of non-gliomas

Disease Types & Epidemiology

How common is the disease?

A primary brain tumor is a mass of abnormal cells that start in the brain. These pathological formations can arise from brain cells, the meninges (membranes) around the brain, nerves, or glands.

Primary brain tumors can be benign or malignant. Being a benign tumor means accumulating a group of visibly (under a microscope) normal cells. Benign brain tumors grow slowly and stay in their capsule. On the other side, malignant brain tumors (called cancer) grow rapidly and typically invade (infiltrative pattern) surrounding the healthy brain (do not have a capsule around). Brain cancer is life-threatening due to the changes it causes to the vital structures of the brain [hopkinsmedicine.org].

Non-glioma origin of the primary brain tumors means that the disease arises from any other cells in the central nervous system (CNS) that are not from the glia “supportive” group.

The most frequent non-glial brain tumors are meningiomas, which develop from the meninges and adenomas of the pituitary gland. Other types include ependymoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, medulloblastoma, and the rest, which are rare tumors arising mainly in children [esmo.org].

According to the National Brain Tumor Society, one million Americans are living with a brain tumor. Around 94,000 U.S. citizens receive a primary brain tumor diagnosis every year, and 5.7% of them are children ages 0-19 years [braintumor.org].

Due to the wide variety of non-glial cells, including those that form cartilages, gland tissue, vessels, or other anatomical structures in the brain area, these tumors are combined into a joint list, ranging from low to high malignancy grade risk according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Brain Tumor Grades.

Grade I brain tumors are the least malignant (benign), slow growing, accessible for radical surgical curation alone, non-infiltrative (growth in its capsule), patients have the best long-term survival rates (for example, craniopharyngioma, gangliocytoma). Grade II brain tumors are still relatively slow-growing, somewhat infiltrative (expand into surrounding tissue), and sometimes may recur (pineocytoma). Brain tumors at grade III are malignant, infiltrative and tend to recur at a higher rate. Non-gliomas grade IV are the most malignant tumors that have fast and aggressive growth, widely infiltrative, rapidly recur, and tend to stimulate necrosis (cell death) in CNS actively (pineoblastoma, medulloblastoma) [aans.org].

Brain tumor diagnosis usually involves:

- A neurological exam,

- Neuro-imaging with a CT or MRI,

- A Brain biopsy.

- PET scans, which are advanced imaging techniques used to effectively detect brain tumors

A treatment approach may vary between the tumor types since the lesions have different locations in the CNS, accessibility for the surgical approach, and targeted therapy sensitivity [hopkinsmedicine.org]. That’s why non-glioma brain tumors are discussed below separately.

Typically benign primary non-glioma brain tumors

Meningioma

Meningioma ranks as the most prevalent type of primary brain tumor, making up over 30% of these cases. These tumors develop from the meninges, the three protective layers of tissue surrounding the brain beneath the skull. They occur less frequently in the spine. Most often, a single tumor is found, but multiple meningiomas also happen.

Risk factors for meningioma include prior radiation exposure to the head and a genetic disorder called “neurofibromatosis type 2”, which affects the nervous system and the skin; however, meningiomas also occur in people who have no risk factors.

A variety of symptoms can occur, depending on the tumor’s location. The most common indications are headaches, weakness on one side, seizures, personality and behavioral changes, and confusion. Neuro-imaging (scanning) with a CT or MRI is used to evaluate the location of the tumor.

Grade I meningioma

Approximately 85% of meningiomas are benign and grow slowly (grade I). Because they grow slowly, they can grow quite large before symptoms become noticeable. Symptoms are caused by compression rather than by the tumor growing into brain tissue.

If the tumor is accessible, the standard treatment for meningiomas is surgery. During the procedure, the surgeon will try to remove the tumor, the portion of the dura mater (the outermost layer of the meninges) that the lesion is attached to, and any bone that is involved. Total removal appears critical for long-term tumor control.

Evaluation of the blood supply of the tumor may be done before surgery via neuro-imaging with intravenous contrast (liquid). In some cases, the blood vessels are embolized (purposefully blocked) to facilitate the removal of the tumor.

If the tumor is not entirely removed, radiation therapy or radiosurgery may occur after surgery. Surgery may not be recommended for some patients due to the deep location of the lesion. Long-term, close observation with scans is typically recommended for patients who have no symptoms (usually meaning they have been diagnosed coincidentally), for patients with minor symptoms of long duration, and for patients who cannot receive surgery due to the location of the tumor. An alternative includes focused radiation, also called “stereotactic radiosurgery.”

Grade II (atypical) and grade III (anaplastic) meningiomas

They represent less than 5% of meningiomas. Radiation therapy is indicated following surgery if any residual tumor is present (grade II) or regardless of whether residual tumor is present.

Meningiomas may recur as a slow-growing tumor or sometimes as a more rapid-growing, higher-grade tumor. Recurrent tumors are treated similarly, with surgery followed by either standard radiation therapy or radiosurgery, regardless of the grade of the meningioma. Chemotherapy and biological agents are being studied for recurrent meningioma. Hormone therapy does not appear effective.

Pituitary adenoma

A pituitary adenoma is the most frequent form of the pituitary tumor, which is responsible for hormone synthesis in the CNS. Adenomas account for approximately 10% of all primary brain tumors. Less than 0.2% of them are cancerous [cancer.net]. Pituitary adenomas can occur in individuals of any age.

50% of pituitary adenomas are endocrine-active, producing excessive amounts of hormones, leading to hormonal imbalances that impact various bodily functions. The symptoms of pituitary adenoma may include headache, vision deficit, menstrual irregularities, lactation, weight gain, easy bleeding or bruising, erectile dysfunction, heat intolerance, and change in bone structure, especially enlargement in the face and hands. Excessive adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production leads to Cushing’s disease due to increased corticosteroids released from adrenal glands. Cushing’s disease presents with upper body obesity, severe fatigue, muscular weakness, high blood pressure and high glucose (sugar) levels, reduced libido and fertility in men, irritability, and anxiety. The rest 50% of pituitary adenomas are endocrine-inactive or non-secreting.

There are three types of treatment used for pituitary tumors [hopkinsmedicine.org]:

- Surgical removal of the tumor through the nasal cavity (transsphenoidal approach) – for small endocrine-active lesions;

- Except for prolactinomas, which are treated with dopamine agonist medication (cabergoline, bromocriptine) for tumor shrinkage;

- Radiation therapy using high-dose X-rays to kill tumor cells – external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and stereotactic radiosurgery.

Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngioma is a non-malignant tumor arising from small nests of cells near the pituitary stalk. Craniopharyngiomas represent 2–5% of all primary brain tumors and 5–10% of childhood brain tumors.

Most symptoms of this tumor result from increased intracranial pressure due to obstruction of the foramen of Monro (one of the small tunnels through which cerebrospinal fluid exits the inner brain space called ventricles). Other symptoms result from pressure on the optic tract (vision impairment) and pituitary gland (delayed development and obesity).

Surgery to remove the tumor is usually the first step in treatment. If hydrocephalus (brain swelling) is present, a shunt may be placed during surgery. That shunt will help drain excess cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain. A form of radiation therapy may be suggested if all of the visible tumor tissue cannot be removed. This intervention may include a focused form of radiation, such as radiosurgery or conformal radiation.

Schwannoma

Acoustic neuromas, also known as vestibular schwannomas, are benign, slow-growing tumors that form on the nerve linking the ear to the brain. They account for less than 8% of all primary brain tumors and typically manifest with hearing loss, ringing in ears, and balance problems in middle-aged adults. These tumors develop on the nerve sheath—the protective layer enveloping nerve fibers—and commonly result in hearing loss. Additionally, schwannomas can impact the trigeminal nerve, leading to a rarer form known as trigeminal schwannomas, which may induce facial pain.

Diagnostic work-up includes a brain MRI or CT of the head to determine if the location of the tumor is surgery-eligible or not.

Surgery through the ear (translabyrinthine approach) is made if the entire large tumor or as much of it can be removed safely. Because a portion (cochlea) of the inner ear is removed during this procedure, hearing is lost in that ear, but balance function is left unaffected if the tumor is small (< 1 cm in diameter) retrosigmoid or middle fossa approach can be used to preserve the hearing.

Post-surgery, patients typically remain in the hospital for several days to allow for recovery under medical supervision, where doctors can monitor and address symptoms such as pain and dizziness. If the surgery impacts hearing, medical professionals can assist the patient in exploring hearing rehabilitation options. Balance recovery occurs gradually, and most individuals are able to resume work within 8 to 12 weeks.

If the surgery is not an option due to deep localization of the tumor or in a patient with a complicated clinical state, stereotactic radiation (Gamma Knife<sup>®</sup>, Linear Accelerator technique (LINAC), Proton Beam approach) is an option of choice [anausa.org].

Once radiation has been used to treat the acoustic neuroma, surveillance imaging, typically with MRI scans, should be performed for at least ten years after the treatment to ensure that the tumor does not continue to show any signs of growth that would require further treatment.

Typically, malignant non-glioma brain tumors

Medulloblastoma

Medulloblastomas represent about 7% of brain tumors in children and adolescents (ages 0-19). Medulloblastomas are always located in the cerebellum, so the symptoms they cause are associated with poor movement coordination, imbalanced walking, drowsiness, vomiting, headache, and nausea.

Medulloblastoma is a fast-growing, high-grade tumor that frequently spreads to other parts of the central nervous system. It is uncommon for medulloblastomas to spread outside the brain and spinal cord. At diagnosis (and during and after treatment), testing will also be done to check for possible tumor spread, including an MRI of the spine and a cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Treatment consists of surgical removal of as many tumors as possible, radiation, and chemotherapy.

After surgery, radiation to the tumor area followed by a lower dose of radiation to the entire brain and spinal cord is typically used for older children, for adults who show no sign of the tumor spreading, and for patients who had most of the tumor removed. Very young children are often treated with chemotherapy instead of radiation.

Chemotherapy generally follows radiation therapy. The most commonly used agents include a combination of cisplatin and vincristine with either cyclophosphamide or CCNU. Other drugs, such as etoposide, have also shown activity against the tumor.

There is no standard treatment for recurrent tumors. Some patients with a recurrent tumor who show good response to chemotherapy may benefit from high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant.