Introduction

Atrial flutter (AFL) is a common atrial arrhythmia that can be associated with atrial fibrillation. Risk factors for this atrial tachyarrhythmia are common as with all cardiovascular diseases (smoking, sedentary lifestyle, impaired eating habits, etc.), but this atrial tachyarrhythmia can also be a long-term complication of any atrial surgical procedure, both open surgery and catheter ablation, which grants it a special place among other heart rhythm disorders.

Classification and pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of this rhythm disorder, as in atrial fibrillation, involves a so-called "re-entry" mechanism. Instead of electrical excitation spreading linearly from the sinus node to the atria and then to the ventricles as in a normal sinus rhythm, it forms a continuously rotating loop, causing more frequent atrial contractions. Unlike atrial fibrillation, AFL has a different re-entry pattern, which is classified as a macro-re-entrant tachycardia, meaning the excitation cycle encircles larger anatomical structures than in atrial fibrillation. Historically, AFL has been divided into types I and II according to the ability of high frequency atrial pacing to cease arrhythmia. However, the modern classification used in Europe distinguishes between macro-re-entrant atrial tachycardias (MRAT), which include cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI)-dependent and non-CTI-dependent types.

CTI-dependent MRAT, also known as "typical atrial flutter," occurs when the re-entry focus lays around the tricuspid valve ring in the area of the CTI. The frequency of atrial contractions is from 240 to 350 per minute, and the frequency of ventricular contractions (heart rate) will depend on conduction through the atrioventricular (AV) node. When each atrial excitation is conducted through the AV node (1:1 conduction) it results in a very high heart rate that can lead to debilitating symptoms or even syncope or hemodynamic instability. The input/output ratio may be even (2:1, 4:1), which is more common, but odd ratios (3:1, 5:1) can be present. If the frequency of ventricular contraction is greater than 100 beats per minute (greater than 80 beats per minute for patients with heart failure), then this form is called AFL with rapid ventricular response; if the heart rate is lower, AFL with low ventricular response is detected. Heart rate between 60 and 80 (100) beats per minute can be comparable to normal heart rate, and a heart rate below 60 beats per minute can be classified as bradycardia as it brings all the concomitant symptoms.

If the focus of macro re-entry is located in the left atrium, then this type of tachycardia was previously known as left atrial flutter. If the focus is located around scar structures after heart surgery (for example, for heart valve disease or pulmonary vein isolation), this type was previously referred to as lesion atrial re-entry or incisional atrial tachycardia. All other types of atrial tachycardia with macro re-entry (as a result of fibrotic processes in the atrial myocardium), were called atypical atrial flutter. This entire group of tachyarrhythmias now belongs to non-CTI atrial tachycardias. The frequency of atrial contraction in this case can exceed 350 beats per minute and irregular conduction is more common, leading to atrial fibrillation. New classification is based on the difference in surgical treatment (catheter ablation), which, for the non-CTI MRAT group requires an extended mapping. However, AFL may not always be regular. Sometimes, variable conduction may occur with alternating or seemingly random patterns. In such cases, auscultation or pulse monitoring can make it difficult to differentiate from atrial fibrillation.

Physical examination, symptoms and diagnosis

The most common symptom of AFL is a sensation of a rapid heartbeat or palpitations (mostly for AFL with alternating conduction). The higher the heart rate, the more debilitating the symptoms are. Other symptoms may include dyspnea, chest pain, dizziness, and even loss of consciousness due to hypotension caused by this rhythm disorder. However, sometimes AFL with normal ventricular response can cause little to no symptoms. With auscultation of the heart, this rhythm disturbance with normal ventricular response can easily be confused with a normal rhythm because of its regularity. It causes fewer symptoms but is still far from a normal sinus rhythm because it does not have the variability inherent in a normal sinus rhythm (dependence on breathing, full adaptation to exercise, or sleep cycles), so it may affect exercise tolerance and quality of life.

As even AFL with normal ventricular response may require anticoagulation, in patients after atrial procedures, an active approach may be taken and an active search for asymptomatic AFL may be required. Generally, AFL is diagnosed using ECG, recorded during the paroxysm, or using recorders such as Holter monitoring, loop recorders, artificial pacemakers, or ECG-recording watches. Sometimes the diagnosis can be challenging, as it can mimic other conditions such as ventricular tachycardia (if conducted with bundle branch block), atrioventricular arrhythmias, or atrial fibrillation. But the CTI-dependent MRAT usually has its own unique ECG pattern, which makes it relatively easy to diagnose.

Treatment

Pharmacological and surgical (catheter ablation)

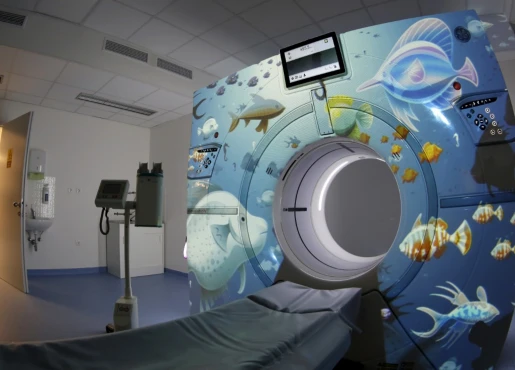

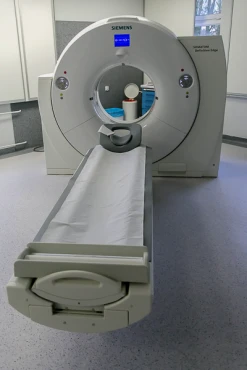

It is recommended that the sinus rhythm be maintained and ablation performed in all patients with symptomatic CTI-MRAT and with symptomatic recurrent non-CTI-MRAT (especially in patients with heart failure). Ablation procedure is performed under local anesthesia in a special facility called electrophysiology lab. During this procedure, femoral vein access is performed and special catheters are placed into the right atrium under fluoroscopy control. In the case of CTI-MRAT, ablation is performed at the cavotricuspid isthmus, but in the case of non-CTI-MRAT, an extended activation mapping is required in order to localize the substrate area using a 3D navigation system. In the case of concomitant atrial fibrillation or left atrial non-CTI-MRAT a transseptal puncture is required in order to access the left atrium. After the substrate area is determined, radiofrequency ablation is performed. The recovery period for this procedure is relatively short. Ablation procedure is the first line treatment for MRAT.

Pharmacological treatment for atrial flutter is limited and only amiodarone has been approved by the European Society of Cardiology for maintaining the rhythm. This medication has a number of limitations on its use. The American College of Cardiology has also approved the use of sotalol and allowed the use of flecainide and propafenone. These medications also have limitations, with sotalol being heart failure with low ejection fraction, and for other two medications having structural heart disease and coronary artery disease. Pharmacological treatment can be challenging as AFL is less responsive to antiarrhythmic drugs compared to atrial fibrillation.

For the AFL with normal ventricular response (spontaneous or on the background of treatment), a frequency management strategy may be chosen. However, as mentioned above, even though with this form, the heart rate is close to normal and the rhythm is regular, it still is not a physiological rhythm. This means that this arrhythmia may affect exercise tolerance and patient's well-being. To manage heart rate, beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers can be used.

If these methods are not successful, “ablation and pacing” strategy may be considered – ablation of the AV node with pre-implanted artificial pacemaker. This procedure is associated with risks inherent in pacemaker implantation.

If a patient already has an implanted pacemaker, type I atrial flutter may be ceased by rapid atrial pacing. As for any other type of hemodynamically significant tachycardia, synchronized cardioversion can be used for acute treatment.

Anticoagulation therapy

Anticoagulant therapy is recommended for patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation according to the principles of atrial fibrillation treatment. To do so, the risks of thrombosis and bleeding are calculated using special scales, and a decision is made about whether to use anticoagulants or not. Generally, anticoagulation is indicated for most patients except young people without concomitant conditions or patients with very high bleeding risk. For people with CTI-MRAT only, there is no consensus on whether or not to prescribe anticoagulant medications. The American College of Cardiology recommends following the principles for treating atrial fibrillation, while the European Society of Cardiology takes a more flexible approach. Anticoagulants include vitamin K antagonists (warfarin) or new oral anticoagulants, comparable in efficiency. The decision about the type of anticoagulant used depends on concomitant diseases (impaired renal function, or the presence of a prosthetic valve), bleeding risk and even body mass and age. It is important to mention that aspirin alone is not indicated for anticoagulation in patients with AFL or atrial fibrillation. There are certain situations when it can be combined with anticoagulants though.

Conclusion

In general, AFL is not a separate disease. It often coexists with other cardiovascular conditions, and treatment requires not only the correct use of surgical and pharmacological techniques for treating arrhythmias but also the correction of concomitant cardiac conditions and risk factors.